Chapter 1: Learn how pervasive consumer concerns about data privacy, unethical ad-driven business models, and the imbalance of power in digital interactions highlight the need for trust-building through transparency and regulation.

Chapter 8: Learn how AI’s rapid advancement and widespread adoption present both opportunities and challenges, requiring trust and ethical implementation for responsible deployment. Key concerns include privacy, accountability, transparency, bias, and regulatory adaptation, emphasizing the need for robust governance frameworks, explainable AI, and stakeholder trust to ensure AI’s positive societal impact.

Content in this chapter

Innovations in digital advertising and their associated business models have emerged largely through technological advancement, raising essential questions about user trust and data privacy (Zuboff, 2019; Richards & Hartzog, 2020). While organizations and their data science teams continue developing sophisticated solutions for marketing optimization, operational efficiency, and service enhancement, research suggests that sustainable digital trust requires a customer-centric approach beyond technical capabilities (Kaptein et al., 2015).

Understanding digital consumer behaviour and decision-making processes is crucial for building genuine trust relationships. Recent findings in neuroeconomics and behavioural economics have revolutionized our understanding of how individuals make decisions under uncertainty – the fundamental context in which trust develops (Riedl & Javor, 2012). Research using functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) has revealed that trust decisions activate specific neural networks, particularly in the striatum and prefrontal cortex. This suggests that trust formation involves both emotional and cognitive processes.

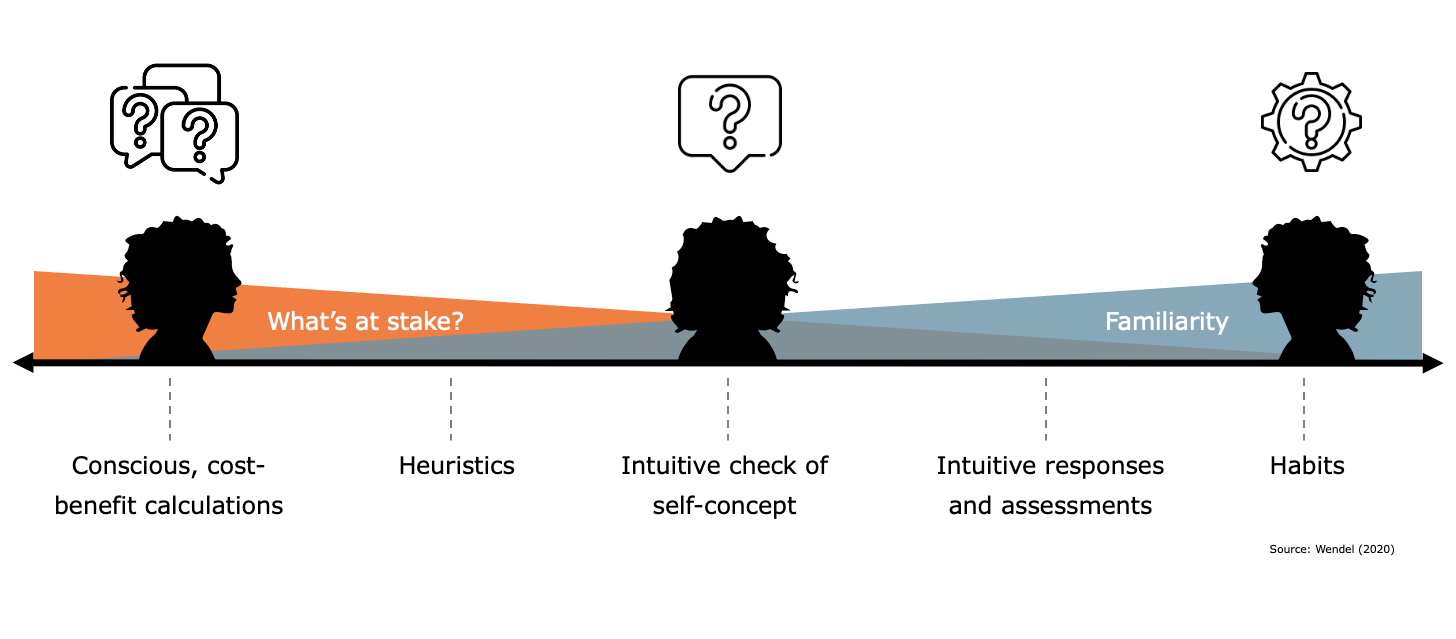

The widespread sharing of personal data online, often without clear compensation or understanding of future implications, appears to contradict traditional economic theories of rational decision-making (the Homo Economicus model). However, contemporary behavioural economics research has demonstrated that human decision-making is inherently bounded in its rationality (Thaler, 2016; Simon, 1982). Individuals frequently rely on cognitive shortcuts (heuristics) and are influenced by contextual factors, emotional states, and social cues when making privacy-related decisions (Acquisti et al., 2015). This growing body of research provides crucial insights into the neurological and psychological mechanisms underlying decision-making under uncertainty. Understanding these cognitive limitations and biases is essential for developing digital environments that promote genuine trust rather than exploit psychological vulnerabilities. Recent studies have shown that transparency in data practices and user control over personal information significantly influence trust formation in digital contexts (Waldman, 2018; Martin et al., 2023).

Towards Trust-Based Marketing

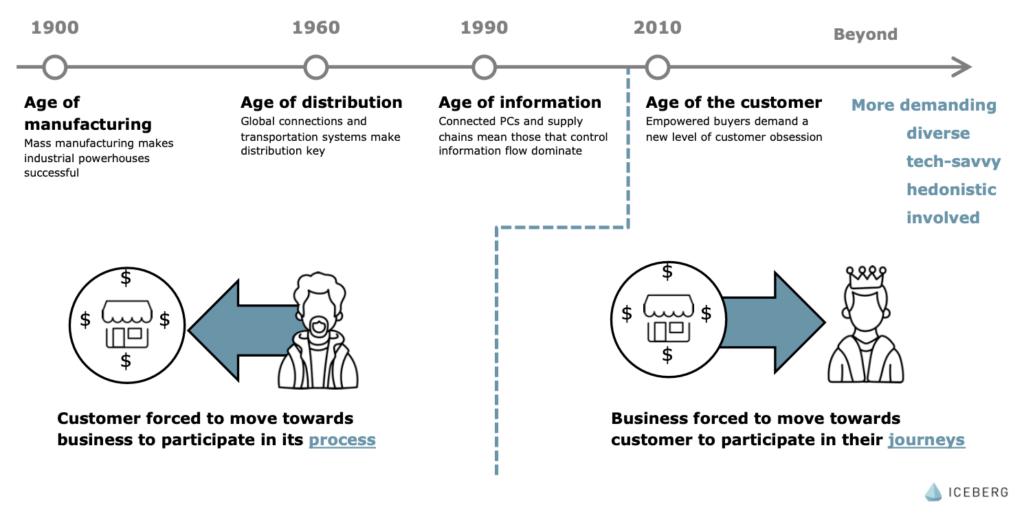

Enabled by digital technologies and social platforms, contemporary consumers have become increasingly sophisticated and challenging to understand through traditional marketing approaches (Lamberton & Stephen, 2016; Kozinets, 2019). To maintain competitive advantage, organizations must expand beyond conventional customer analytics to comprehend consumers within their complex social network ecosystems and digital environments (Kuma & Reinartz, 2016). While information and communication technologies have achieved widespread adoption and increasing sophistication, businesses must fundamentally reimagine their marketing strategies to address emerging consumer characteristics and behaviours. Research demonstrates that technological advancement has facilitated the rise of an empowered global consumer characterized by unprecedented access to information, peer recommendations, and market alternatives (Denegri-Knott & Zwick, 2012; Belk, 2013):

Consumers have evolved into more sophisticated and knowledgeable market participants, demonstrating increased technological literacy and greater control over their consumption processes (Kozinets, 2019; Hennig-Thurau et al., 2010). Digital transformation has facilitated the emergence of interconnected consumer networks that actively generate content and form digital communities, fundamentally altering traditional market dynamics (Belk, 2013).

The initial digital transformation phase provided consumers unprecedented access to information, ostensibly enhancing their decision-making capabilities (Acquisti et al., 2016). However, the current digital landscape presents a paradox: while information is abundant, the complexity of market practices – such as algorithmic pricing and personalization – has created new forms of information asymmetry and consumer confusion (Martin & Murphy, 2017). This evolution allows organisations to differentiate themselves through transparent practices and trust-building initiatives, particularly as consumers struggle with information overload and decision fatigue (Waldman, 2018).

Digital consumers demonstrate heightened expectations and more sophisticated demands than traditional consumers (Rose et al., 2012). Research indicates that modern consumers routinely use cross-industry price comparisons and service-quality benchmarking enabled by digital platforms and comparison tools (Kumar & Reinartz, 2016). Studies show these consumers expect consistent service standards across channels and tangible recognition for their loyalty, with convenience, flexibility, and personalization now considered basic requirements rather than differentiators (Wilson et al., 2017).

Recent research in consumer psychology reveals an increasing shift toward hedonistic consumption patterns in digital environments, characterized by expectations of immediate gratification and seamless experiences (Holbrook & Hirschman, 1982). This evolution necessitates a fundamental shift toward human-centred design and service delivery approaches (Parasuraman et al., 2005). Data suggests that organizations failing to prioritize user experience and emotional satisfaction face significant customer attrition risks in today’s competitive digital marketplace (Duhachek, 2005).

Establishing an authentic, bidirectional dialogue and sustained customer partnerships has become critical for organizational success in the digital economy (Morgan & Hunt, 1994; Kumar & Reinartz, 2016). The evolution of marketing theory and practice reflects a fundamental shift from traditional transaction-based approaches to relationship-centric models that address the needs of increasingly empowered consumers (Vargo & Lusch, 2004). Studies indicate that organizations must fundamentally reimagine their marketing strategies to align with the emerging paradigm of consumer empowerment and digital engagement (De Keyser et al., 2015).

Contemporary marketing research emphasizes that successful customer relationships in digital environments require transparency, authentic engagement, and value co-creation, moving beyond traditional customer relationship management approaches (Payne & Frow, 2005).

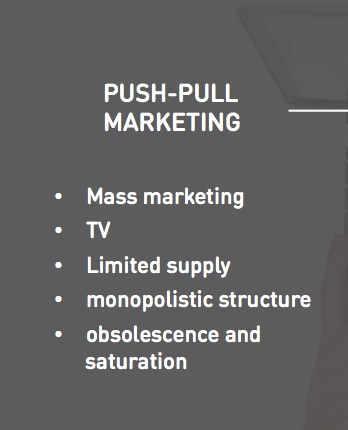

Push-Pull Marketing

Marketing literature distinguishes between two fundamental strategic approaches: Push and Pull strategies (Kotler & Keller, 2023). In push strategies, companies provide incentives to channel members to stock and promote their products, while pull strategies focus on direct consumer advertising (Armstrong & Cunningham, 2024).

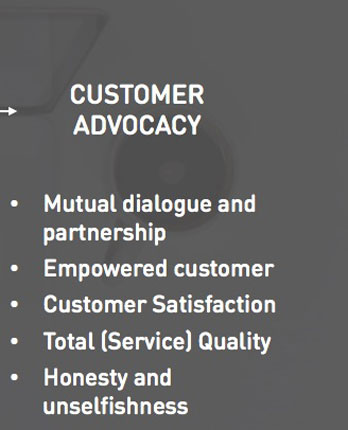

Customer Advocacy

Customer Advocacy represents a strategic evolution in relationship marketing, focused on building deeper customer connections through trust and commitment (Urban, 2022). Advocacy depends on three core elements: mutual transparency, authentic dialogue, and collaborative partnerships (Kumar & Pansari, 2023).

Traditional mass markets, characterized by monopolistic structures, relied heavily on Push-Pull Marketing approaches. In Push strategies, companies provide monetary and non-monetary incentives to channel partners to include products in their assortment. This approach enables markets to increase product visibility, and, as Szeliga (1996) argued, enhanced differentiation from competitors’ products serves as a crucial stimulus for consumer purchase decisions. Research has shown that such strategic differentiation through channel partner activation remains effective even in today’s digital marketplace (Gielens & Steenkamp, 2019).

In contrast, Pull strategies focus on direct-to-consumer advertising to generate brand awareness and demand. Recent studies indicate that when consumers actively seek out products, retailers are motivated to stock these items to meet customer expectations (Kumar & Pansari, 2016). However, implementing effective Pull strategies typically requires significant organizational scale and financial resources to sustain consumer communication campaigns and brand-building initiatives. This resource requirement often limits pure Pull strategies to larger, well-established organizations (Wilson et al., 2017).

Successful strategies often blend push and pull promotional methods, though their relevance has evolved significantly with market conditions (Kumar & Palmatier, 2016). While traditional Push-Pull Marketing was most effective in monopolistic markets with limited supply, digital transformation has particularly revitalized pull strategies through new channels and consumer touchpoints (Wilson, 2018).

The digital marketplace has enabled innovative applications of pull marketing, particularly in the music streaming industry. Research examining platforms like Spotify and Apple Music demonstrates how user-generated playlists are powerful pull marketing tools (Morris, 2015; Morris & Powers, 2015). This shift from traditional album-based distribution to playlist-centric consumption represents a fundamental transformation in how consumers discover and share music, creating organic promotion through social networks. Studies show that this user-driven content curation significantly influences consumer behaviour and engagement patterns in digital entertainment markets.

The emergence of digital technologies, particularly the internet, enabled genuine customer dialogue and unprecedented access to consumer behavioural data. This technological evolution facilitated the rise of Customer Relationship Marketing (CRM), which places individual customer data and interactions at the centre of communication strategies. Unlike traditional Push-Pull Marketing, which focuses on short-term awareness and sales, CRM emphasizes building sustained customer engagement and loyalty through personalized interactions.

Successful implementation of this paradigm shift requires sophisticated, integrated IT systems capable of capturing and leveraging customer knowledge across all touchpoints (Kumar & Reinartz, 2016). Research indicates that organizations implementing such CRM infrastructures achieve significantly higher customer lifetime value and brand equity than those maintaining traditional transaction-focused approaches (Morgan & Hunt, 1994).

“Far from being foolish, the honesty of advocacy reflects the reality that customers will learn the truth anyway. If a company is distorting the truth, customers will detect the falsehoods and act accordingly.” (Urban 2005).

Building authentic trust and developing genuine customer partnerships requires organizations to advance beyond traditional marketing approaches (Urban, 2005a; Morgan & Hunt, 1994). MIT Sloan Professor Glen Urban pioneered a significant advancement in marketing theory through the concept of Customer Advocacy, which represents an evolution beyond traditional relationship marketing approaches (2005b). This framework responds directly to the characteristics of increasingly empowered, knowledgeable consumers in digital markets by emphasizing trust-building and authentic partnerships (Lawer & Knox, 2023).

Research demonstrates that Customer Advocacy focuses on developing deeper customer relationships through three key elements: mutual transparency, sustained dialogue, and collaborative partnerships. This approach extends beyond conventional market orientation to address contemporary drivers of consumer choice, involvement, and knowledge in digital environments. Gartner presents a set of case studies for customer advocacy here.

Customer advocacy builds on the mindset and tools of the CRM approach, with total quality and customer satisfaction as a foundation. Companies that follow this strategy act as honest, unselfish advocates for customers. This includes providing the customer with the best offer even if it comes from a competitor (Urban 2005b). Following this approach in trust-based marketing is essential to engender online trust effectively.

The discussed advances in information and communications technology have given rise to a new, more empowered consumer. The increasing importance and reliance on data not only changed the way companies produce and provide services and products, but also the way customers make decisions about their consumption and behaviours. Traditional theories in social sciences are no longer able to explain customer behavior in a digital world.

To understand the minds of digital customers (and eventually how digital trust works), marketing strategists need to draw on new findings from neuroscience, experimental and behavioral economics, and cognitive and social psychology. The rest of this chapter is dedicated to this promising, interdisciplinary field of science: Neuroeconomics.

Consumer neuroscience research applies tools and theories from neuroscience to better understand decision-making and related processes. Drawing on new methods and technology (such as functional magnetic resonance imaging, fMRI), this scientific discipline can make important contributions to consumer behavior and marketing (Plassmann et al. 2015). Neuroimaging can help turn the black box of the consumer’s mind into an aquarium. It can help validate, refine, and extend marketing theories by providing insights into the underlying mechanisms. The next sections provide an easy-to-understand introduction to neuroscience and the core concepts of human decision-making.

Let’s address the Elephant in the room

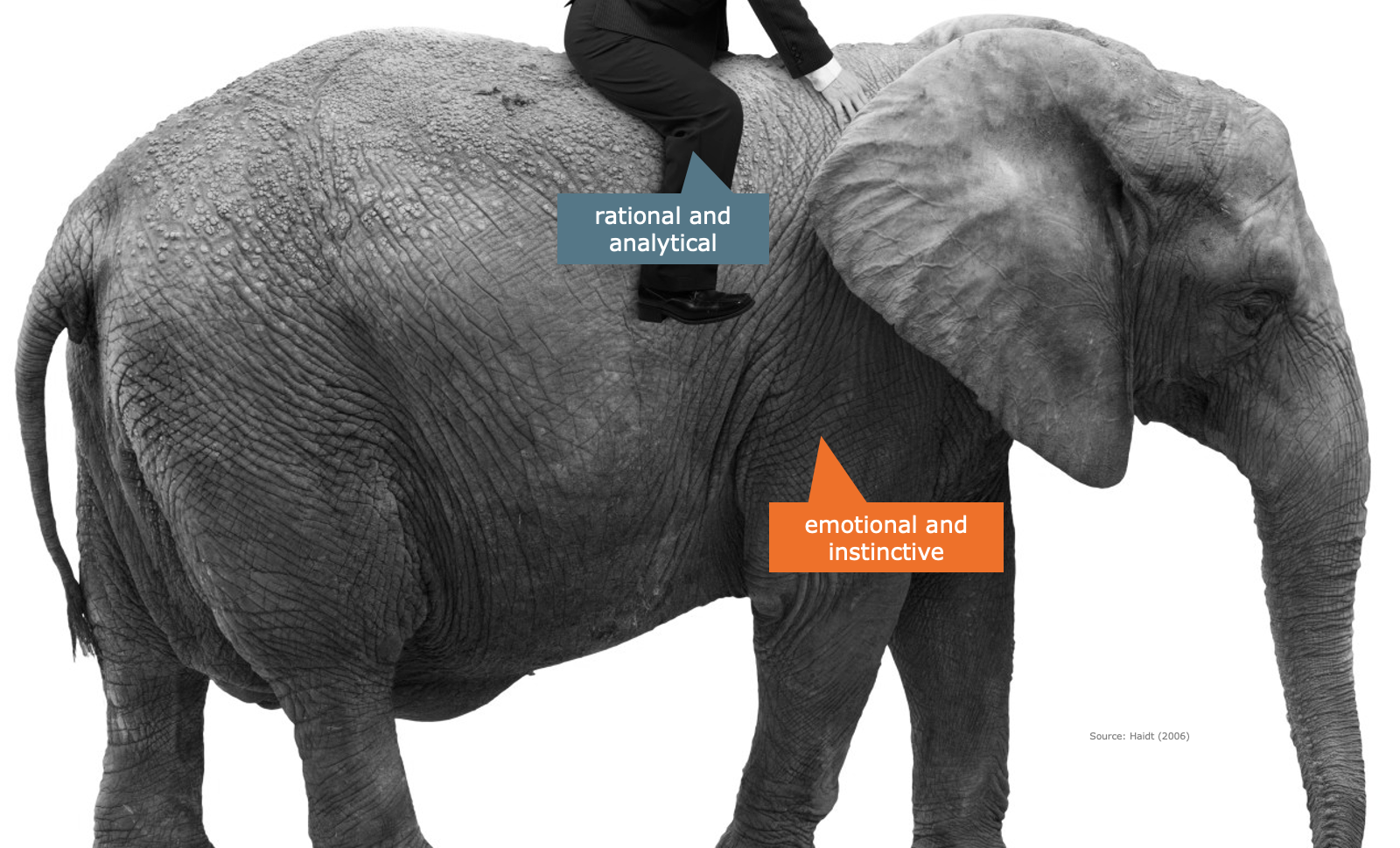

The Elephant and Rider metaphor, introduced by psychologist Jonathan Haidt in his book The Happiness Hypothesis, illustrates the relationship between our emotional, intuitive mind and our rational, reasoning mind (2006).

The Elephant and Rider metaphor can be effectively applied to the context of trust in artificial intelligence (AI) by understanding how emotional intuition (Elephant) and rational reasoning (Rider) influence our perception and acceptance of AI. Trust in AI systems involves both the intuitive, emotional response to the technology and the rational evaluation of its performance, reliability, and ethical alignment.

The Elephant (emotions):

People’s trust in AI often begins with emotional reactions—fear, excitement, or scepticism. Concerns about job displacement, bias, or lack of transparency can evoke resistance, regardless of the system’s actual capabilities.

The Rider (reason):

The rational mind evaluates AI through technical metrics like accuracy, fairness, and explainability. Even if the system performs well, trust may falter if people feel emotionally uneasy about its use or implications.

Trust-building requires alignment:

Successful adoption of AI hinges on aligning the emotional (Elephant) and rational (Rider) perspectives. For instance, intuitive fears of bias can be addressed by rationally demonstrating fairness through transparent algorithms and policies.

Emotional trust precedes rational trust:

Without addressing emotional concerns – such as fears about privacy or loss of control – rational explanations of AI’s benefits may fail to persuade. People need to feel safe before they engage with the logical aspects of the technology.

Overcoming skepticism:

Transparency, relatable design, and user-friendly interfaces can calm the Elephant, reducing emotional barriers. For example, humanizing AI through voice, visuals, or explanations can make it feel less alien.

Preventing blind trust:

The Rider plays a crucial role in ensuring that emotional trust in AI doesn’t lead to complacency. Rational scrutiny ensures that systems are genuinely trustworthy and not just perceived as such.

Bias in both Elephant and Rider:

Cognitive biases influence both the emotional and rational responses to AI, potentially distorting trust. Awareness and education about these biases can help calibrate perceptions.

The ultimate goal:

To build trust in AI, organizations must design systems that appeal to both the intuitive and rational dimensions of human nature, creating technologies that are not only effective but also emotionally acceptable and ethically sound.

Shared decision-making:

Framing AI as a collaborative tool rather than a replacement can help balance the roles of the Elephant and Rider, fostering trust and acceptance.

Building a feedback loop:

Trust grows when users see AI delivering consistent and fair outcomes, reinforcing the Rider’s logical confidence and the Elephant’s emotional comfort.

A. Two systems of the brain

An understanding of the basic structure and mechanisms of the human brain is key to understand the digital customers mind. The most fundamental insight in this context is the fact that our thinking relies on two distinct systems – dual-process accounts of reasoning. The first system operates automatically and quickly, with little or no effort and no sense of voluntary control. The second operates more slowly and allocates attention to the effortful mental activities that demand it. Popular science refers to these systems as cool and hot thinking (Mischel, 2014) or simply system 1 and system 2 (Kahneman, 2011).

Research has come a long way in analyzing and differentiating these two systems. Whereas the neurobiological approach divides the roles of information processing along anatomical lines (into the limbic system and the prefrontal cortex), the neuropsychological approach uses a dual-mode of thinking and is reluctant to assign information-processing functions to a specific organ within the brain. When thinking about the brain, the critical part is to understand the research on both sides of the issue and to create a mental model that helps explain how individuals process information.

The two systems of the brain can be easily explained by studying the famous Stanford marshmallow experiment conducted in the late 1960s by psychologist Walter Mischel. In these studies, Mischel tested children’s ability for self-control. Children were offered a choice between one small reward provided immediately and two small rewards if they waited for a short period. These experiments showed that children with high self-control were more successful in life than those with low self-control. In addition, Mischel showed that this ability can be easily trained and that effective strategies can increase one’s self-control. However, we will focus on the brain systems that are active when we are exposed to a stimulus and must make a decision. As shown in the picture below, there are two types of processing – hot and cool – involving distinct interacting systems (Metcalfe/Mischel, 1999):

The hot system is specialized for quick, emotional processing. It responds based on unconditional or conditional trigger features. Therefore, this system reacts fast and to a certain extent mechanically to emotions, instincts, or drives such as lust, pain, or fear. From an anatomical perspective, we are talking about the limbic system. The area of the brain arose in an early phase of evolution. For our early ancestors, the limbic system was key to effective flight behavior. In a dangerous situation, it is often more effective to react quickly and run than to elaborate a deliberate escape plan. The hot system resembles the unconscious, psychic instance, as defined by Freud, the “id”. A prominent area of the limbic system is the amygdala. It plays a primary role in memory processing, decision-making, and emotional reactions, including appetitive behavior.

The cool, cognitive system developed later in evolution. It is specialized for complex spatiotemporal and episodic representation and thought. The cognitive system is located in the prefrontal cortex. Research shows that this brain region plays an important role in planning complex cognitive behavior, personality expression, decision-making, and moderating social behavior. It orchestrates thoughts and actions in accordance with internal goals. The cool system arose in a later phase of evolution. In the context of the marshmallow experiments, the prefrontal cortex is responsible for the children’s self-control. It allows one to resist stimuli and to make future-oriented decisions.

Knowledge of these two very distinct systems of the brain helps us understand the consumer’s mind. When prompted to provide personal data online, a customer will always process it through both systems. It is key to recognize that the cool and hot systems always influence and compete with each other. When we face a stressful situation, the cognitive system powers down and allocates resources to the hot system. As with the children in the Stanford experiments, digital consumers need to be able to resist temptations and cool allures to make rational, deliberate decisions. Professor Mischel identifies a set of powerful strategies that help individuals increase their self-control. Among these is the strategy of reflecting on one’s situation from another person’s perspective. The cool system can more easily be activated when a hot decision is made for another person. This may explain the success of online recommendations and third-party endorsements. Users may make incorrect purchase decisions, but their online reviews (e.g., on TripAdvisor) are particular and helpful to others in preventing the same mistakes. Reviewers can offer meaningful recommendations, even if they have not purchased or used the service or product themselves.

Increased sensitivity of online customers regarding privacy and higher competence in dealing with personal data support the activation and, therefore, the weight of the cognitive, so the cold, system. The evolution of the digital mind will make it increasingly more difficult to extract an email address from a visitor with promises of a chance to win an iPhone. Already, users have become more willing to deliberate a robust password instead of a 4-digit number – which was probably the user’s birthday.

An increased sensitivity of online customers regarding privacy and higher competence in dealing with personal data support the activation and therefore the weight of the cognitive, so the cold, system. The evolution of the digital mind will make it increasingly difficult to extract an email address from a visitor who is promised a chance to win an iPhone. Already, users are more willing to use a strong password rather than a 4-digit number, which was probably their birthday.

Building initial trust relies heavily on evaluating existing schemata. Such schemata describe an organized pattern of thought or behavior that organizes categories of information and the relationships among them. Schemata can be seen as memory traces. Incoming data is matched with these available patterns and evaluated within the limbic system. The iceberg trust framework considers the importance of behavioral schemata and the fact that the mentioned mechanism within the hot limbic system can hardly be influenced (see chapter 3). Part of the journey towards a more sustainable approach to personal data is to benevolently support customers in building new competence in dealing with data and, eventually, in developing these schemata.

B. The social brain

Trusting other people or an organization is a highly social act. Our brain must be able to process an enormous amount of information to make a decision about the trustworthiness of another individual. Next to more transparent signals, such as quality seals and recommendations, people consider hidden mental states or traits when deciding to trust. This largely lies within the responsibility of the cool system. However, a more anatomical approach is required to better understand these mechanisms.

As a result of the evolution, the human brain is much larger than those of primates and mammals of similar size. It is particularly the “cool” neocortex that enables human beings to have higher social cognition. The outermost layer of the brain is known to support social interaction by enabling conscious thought, language, behavioral and emotional regulation, and empathy. It enables individuals to understand others’ feelings and intentions. A phenomenon referred to as theory of mind.

The mere size of the neocortex is said to determine the size of the group an individual can socially act in. Robin Dunbar, a professor of evolutionary anthropology at Oxford University, found this correlation between primate brain size and average social group size. He defined a cognitive limit to the number of people with whom one can maintain stable social relationships (Dunbar, 1992). His theory holds that the human brain can manage relationships with only about 150 people. According to a study by Dunbar based on Facebook data, this number remains highly relevant in the digital space.

To better understand the social brain, neuroscientists draw on modern research approaches, such as computational neuroimaging. I had the pleasure of meeting Professor John P. O’Doherty during a PhD seminar in neuroeconomics at the University of Zurich. His research on social cognition shows which brain areas are responsible for social interaction and mentalizing – the process of reflecting on the hidden mental states and intentions of others – in particular (O’Doherty et al., 2013). The study identifies three distinct learning systems that may contribute to social cognition and map onto distinct neuroanatomical substrates (as shown in the picture below).

Observational-reward learning: An agent learns not trough direct experience but instead by observing the stimuli and consequences experienced by another agent.

Action-observational learning: the mere choice of action made by an observee that lead to consequences influence expectations of the observers.

Strategic learning about traits and hidden mental states of others. Only this learning system engages typically social brain areas such as the anterior dorsomedial prefrontal cortex (dmPFC) and the temporoparietal junction (TPJ) as well as the posterior superior temporal sulcus (pSTS).

C. The pain of paying

A third interesting source of insights from neuroeconomics research comes from the findings of INSEAD Marketing Assistant Professor Hilke Plassmann. While traditional economic theory draws on utility theory to explain purchase decisions, behavioural economic theories suggest an additional hedonic process that considers price payment as an immediate displeasure: The pain of paying. In the context of trust, providing personal data can also be considered an act of paying. Hence, providing personal data online is an effective experience that guides online behaviour.

Plassmann’s recent research provides empirical evidence of a higher-order affective pain experience (Plassmann, 2017). “Marketing actions, such as changes in the price of a product, can affect neural representations of experienced pleasantness” (Plassmann et al., 2008). The pain of paying appears to be associated with affective, rather than somatosensory, pain. fMRI results show that affective and somatosensory pain affect different brain areas. The more intense the pain experience, the lower a consumer’s Willingness-to-Pay (WTP). Manipulation of affective pain (e.g., through conceptual priming or drugs) can influence the consumer’s WTP.

These results show the power of contribution neuroscience can make to traditional economic disciplines such as marketing. It gives new and detailed insights into the mechanism of the consumer’s mind. Obviously, marketing specialists have always been aware that customers dislike the process of paying. Transaction data proves consumers spend more when they can pay with credit cards. In addition, the concept of all-inclusive hotels is widely spread and highly appreciated by travellers.

In the context of online trust, marketing specialists need to consider that providing personal data is associated with affective pain. Hence, this perception of affective pain needs to be facilitated to get the customer’s consent and access to the data. A promising strategy is the deliberate timing of data collection. Data can or should be collected along phases of the digital customer lifecycle when a low level of affective pain can be assumed. This topic is covered in the section on timing in Chapter 3.

Trust plays a central role in helping consumers overcome perceptions of risk and insecurity (McKnight, 2002). It is essential to enable business transactions online. When buying a product online or providing personal data, a customer can never be perfectly sure that the transaction will fulfill their expectations and the data provided will not be abused. The information available is always incomplete. Information asymmetry is omnipresent on the World Wide Web. Trust reduces this complexity by facilitating the customer’s decision-making process under uncertainty.

To understand this process, an overview of scientific theories of decision-making under uncertainty is helpful.

Behavioral economics offers an interesting set of theories that help explain how people act under uncertainty. This discipline has been dominated for years by the picture of the homo economicus – an individual who acts rationally, without being influenced by emotion. The homo economics draws on the cool system as described above to align his decisions fully on the maximization of benefit and minimization of cost. However, friends, feelings, and preferences influence even the coolest character in his behavior. As outlined above, our brains are “hard-wired” to interact socially with other human beings. And all these interactions lead to information and eventually to schemata that influence our decisions through the hot system, even before the cool system kicks in. Empowered by technology, consumers have become networked minds and social decision-makers more than ever before (Helbing, 2015). The following section provides a summary of the key concepts that describe economic behavior within the context of the transition from “homo economicus” to “homo socials”:

A. Expected value and utility

The most basic economic theory relies on a purely mathematical view of probability theory. According to the expected value theory, an agent aligns his behavior precisely with the predictions of mathematical probability theory. Behavior is a function of the expectancies one has and the value of the goal toward which one is working. The expected value of an outcome equals the objective probability of occurrence multiplied by the objective value of this outcome.

Although mathematically correct, this equation is not able to reflect reality. Basic findings in psychophysics first suggested that in the real world there is no linear relationship between a stimulus and an outcome – a subjective sensation in this case. Turning on a weak light has a large effect in a dark room. In a fully illuminated room such an increment of light may remain unnoticed. Prominent research in 19th century suggests that for many dimensions the function is logarithmic (Weber-Fechner Law) or a power function (Stevens’ Power-Law)

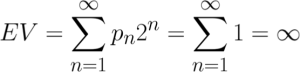

Following this reasoning, economists agreed that a purely mathematical consideration of expected money yields incorrect results and that the relationship between the psychological value and actual cash follows a logarithmic rather than a linear function. It was Swiss scientist Daniel Bernoulli who enhanced expected value theory to the more subjective expected utility theory. Individuals no longer consider the objective Value of an option but rather a subjective equivalent to this value. Utility is a logarithmic function of wealth. This correlation can best be explained by examining the St. Petersburg paradox.

Consider a theoretical game in which a fair coin is tossed. If tail appears the player is paid $2 (assuming an investment of $1). If head appears the coin is tossed again, until tail appears, doubling the initial gain every time the coin is tossed. The paradox is the discrepancy between what people are willing to pay to enter the game and the expected value. According to the expected value theory, the expected gain would be infinite and a rationally acting individual would be willing to play the game at any price if offered the opportunity. People tend to distrust this result.

Bernoulli observed that most people neglect unlikely events that yield the high prizes that lead to an infinite expected value. Most people dislike risk and will choose a sure thing that is less than expected value. Bernoulli’s utility function also simply explains why poor people buy insurance and why richer people sell it to them. Depending on the relative wealth an individual is happy (low wealth) to a premium to transfer risk to another individual (high wealth). The risk aversion is explained by the diminishing marginal value of wealth. Not only the expected value is subject to individual, subjective consideration but also the probability of occurrence.

B. The prospect theory

The subjective expected utility theory is not fully capable of explaining why people will always choose a known probability of winning over an unknown probability of winning even if the known probability is low and the unknown probability could be a guarantee of winning – a key finding also known as the Ellsberg paradox or ambiguity effect.

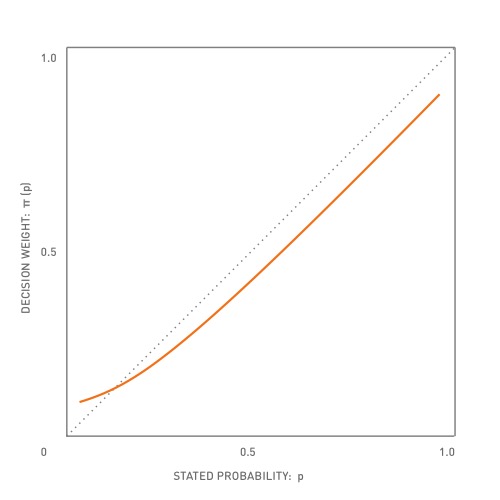

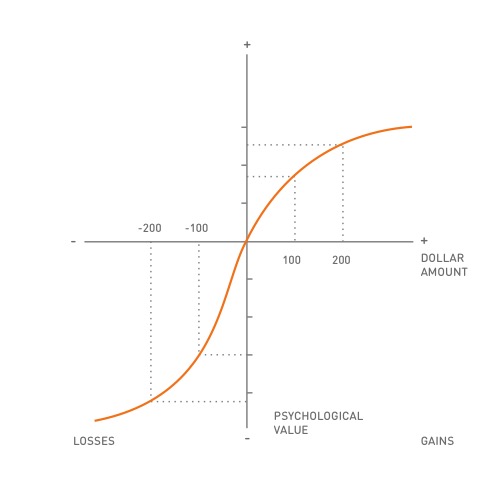

Kahneman and Tversky found that people’s preferences systematically violate the principle the expected utility theory (1979). People just can’t think in terms of a continuum of probabilities. Objective probabilities should rather be considered subjective decision weights. Most people who board an airplane reduce the probability of a crash to zero. But some people don‘t. They overrate the probability of crashing. As shown in the picture below, the decision weights differ slightly from the objective probabilities. Kahneman and Tversky suggest that small probabilities are overrated while middle and large probabilities are underrated. This implies that the probabilities of risky options are underestimated relative to the specific probabilities of winning (certainty effect). The effect increases the preference for a particular positive option (win), thereby leading to risk-averse decision-making. When faced with one specific negative option (loss), people tend to act risk-seeking. A sure loss is very aversive, and this drives people to take the risk. People tend to become risk-seeking when all their options are bad – they have “nothing to lose”.

In their prospect theory, Kahneman and Tversky extend simple utility theory by three mayor elements (1979, 2001):

The principle of diminishing sensitive as described by findings in psychophysics is adapted to the evaluation of changes in wealth.

Drawing on evolutionary history, Kahneman and Tversky suggest that negative expectations loom larger than positive expectations. Survival and reproduction are better assured when threats are treated more urgently than opportunities. This results in a principle of loss aversion.

Thirdly, evaluation according to the prospect theory is relative to a neutral reference point. A decision maker considers prospects using a function that assigns each prospect a value relative to a reference point.

As a result of these principles, the value function under prospect theory is S-shaped. It shows the psychological value gains and losses, which are the “carriers” of value (and not states of wealth). The left side of the steeply sloping graph indicates that the response to losses is stronger than the response to corresponding gains, while both sides of the reference point show diminishing sensitivity. This implies that people are very conscious about little changes around the reference point. Sensitivity to losses or gains is maximal in the very first unit of gain or loss. This explains the commercial success of insurance policies for diamond rings, single flights, or funerals that are slightly insignificant. These are all easier to sell than significant policies like life insurance.

The prospect theory helps to explain several behaviours observed in economics. The different perspectives on looming gains and losses may explain why the same person may buy an insurance policy and a lottery ticket. Furthermore, the prospect theory highlights the implication of the following selection of effects (cognitive bias) that significantly influence decision-making:

Ambiguity effect

People prefer to choose an option with a known probability of a favorable outcome over an option where this probability is unknown. Even if the stock market lures with high returns over time, a risk-averse investor tends to invest money into conservative investments such as government bonds and bank deposits, as opposed to more volatile investments such as stocks and funds.

Certainty effect

As elaborated above when discussing the subjective probability weights, people tend to overweight outcomes that are certain relative to those that are probable. Certain probabilities of winning are preferred compared to risky options. A reduction of a chance of winning results in larger psychological effect when it is done from certainty than from uncertainty. Most people would pay more to remove the only bullet in the gun in a game of Russian Roulette than they would to remove one bullet when there were four in the gun.

Anchoring effect

Individuals judge the frequency, probability, or value of items often in comparison to an anchor point. A customer that considers a product that has a price tag with three different prices considers this a bargain, if the two highest prices on the tag are crossed out. The highest price on the tag may be seen as an anchor.

Framing effect

The framing effect is an example of a cognitive bias, in which people react to a particular choice in different ways depending on how it is presented; e.g. as a loss or as a gain. People tend to avoid risk when a positive frame is presented but seek risks when a negative frame is presented. Risky prospects can be framed in different ways as gains and losses. Framing a prospect as a loss rather than a gain, by changing the reference point, changes the decision due to the properties of the value function. German politicians preferred talking about an austerity package (“Sparpaket”) rather than budget cutting measures that have been inflicted on Greek people in response to recent economic crisis.

Endowment effect

People adjust to their level of ownership. This new level becomes the baseline by which they judge future gains and losses. When we own something, we focus on what we would give up rather than what we could gain. This effect explains the success of sales tactics such as the provision of trail versions and a “30 day money-back guarantee”

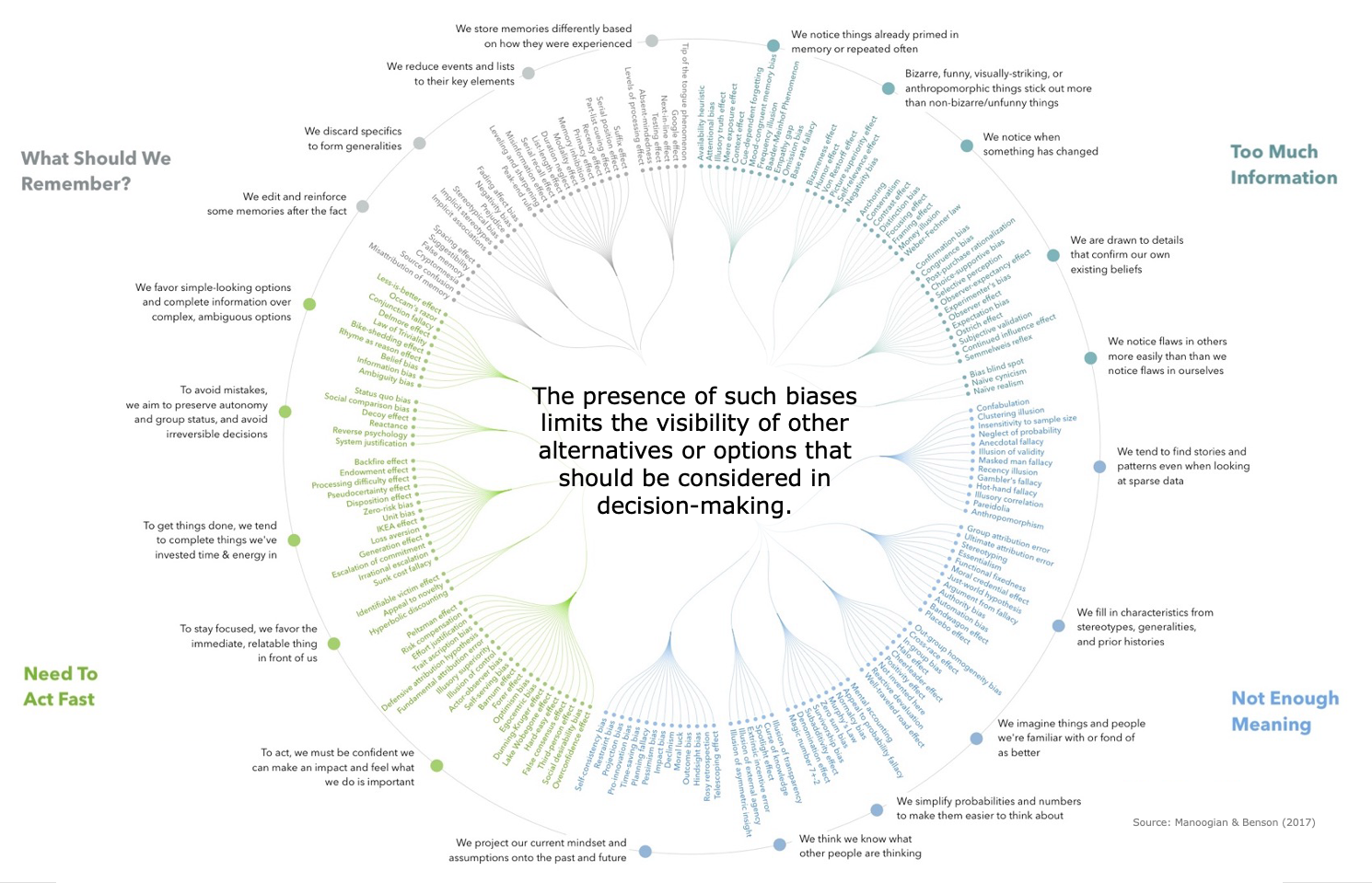

There are hundreds of identified cognitive biases, according to the latest compilations in psychology and behavioural sciences. These biases have been categorized based on decades of research and are commonly grouped by their functions, such as biases related to memory, attention, social interaction, and decision-making (Manoogian & Benson, 2017):

Too much information: The universe contains more information than any individual or system can process, creating inherent limitations for even super-intelligent AI.

Not enough meaning: Transforming raw data into meaningful interpretations relies on subjective connections to past experiences and symbols, which can lead to biased understanding.

Not enough time and resources: The finite time for decision-making prevents thorough analysis, forcing reliance on intuition and heuristics.

Not enough memory: Limited memory capacity, even for advanced AI, necessitates strategic generalization, which introduces distortions.

The presence of such biases limits the visibility of other alternatives or options that should be considered in decision-making.

Visit this tool the University of St. Gallen created to learn about the universe of biases interactively.

To sum things up:

The traditional economic concept of the rationally acting individual is incorrect. Decision-making must be best explained with the theory of bounded rationality (Simon, 1997). People tend to make decisions with particular biases. Understanding these biases provides insights into consumers’ minds and eventually reveals strategies for marketing that influence customer decisions. The prospect theory gives important hints for potential strategies to engender and maintain digital trust:

Pay attention to detail.

Prevent customers from even smallest damages (losses) to trust that can occur for example through minor Data leakage. Sensitivity to losses or gains is maximal in the very first unit of gains or loss. People are very concise about little changes. It is easy to loos someone’s trust but hard to engender trust.

Pay attention to the reference point and framing.

The way agents subjectively frame an outcome or transaction in their mind affects the utility they expect or receive. Companies can actively define – or to a certain extent – manipulate framing.

Pay attention to anchoring.

The estimation of subjective probabilities and values is severely biased by anchoring. Third party endorsements and recommendations can support online trust. This works best when the own brand is compared to an already trustworthy brand (as an anchor). Pay attention to your main message as this would often be the first piece of information and therefore considered an anchor.

Pay attention to ambiguity.

Be transparent whenever possible and provide warranties. Demonstrate accountability. Online customers prefer to choose options with a known probability of a favorable outcome over options where this probability is unknown.

C. Perspectives from behavioral ecology

The prospect theory offers essential insights into the bounded rationality of human decision-making. However, as a descriptive theory, its ability to explain situations like the Ellsberg Paradox is limited.

Decision-making is often much more complex than described in mathematical models of the discussed theories. It is evident from intuition that more specific factors, such as environmental conditions and individual needs, can influence human decision-making.

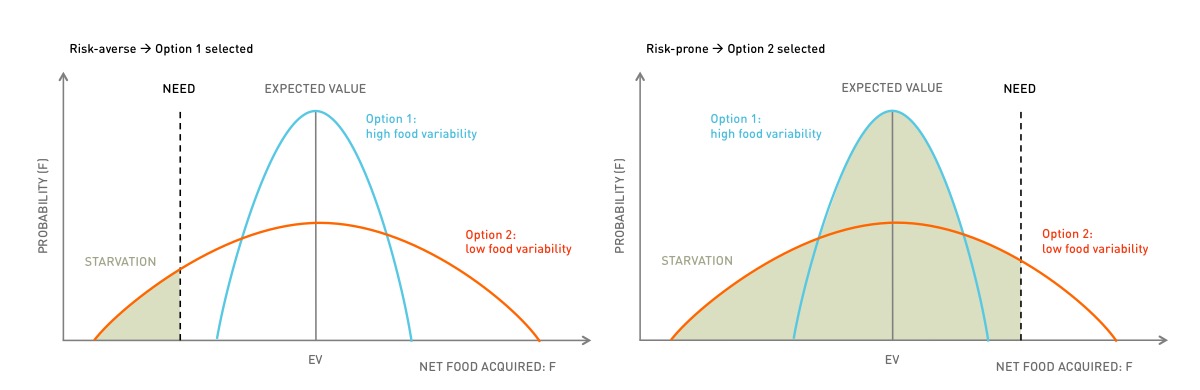

An interesting approach to decision-making originates from research in behavioral ecology. Studies of the foraging behavior of birds showed that animals not only consider utilities and probabilities but also their individual need. Behavioral ecology shows that choosing a risky option can be regarded as an evolutionary stable strategy if the need is higher than the average, expected value of two options (Stephens 1981, Rode et al. 1999). It’s all about minimizing the probability that a current need remains unsatisfied – or in other words: it’s all about survival.

Three parameters seem to be relevant for decision-making when facing two options under uncertainty:

Current need

Average expected value

of each option

The variability of an option

According to the Risk-Sensitive Foraging Theory, animals are trying to maximize the probability of reaching a goal. An animal acts risk-averse if (1) it faces two options with different variability and (2) the risk of not satisfying its need if it chooses the option with high variability (while the option with low variability satisfies its need for certain). Conversely, an animal is risk-prone if its need exceeds the maximum value offered by the low-variability option. It then chooses the option with higher variability and hopes that its needs will be satisfied with a lower probability.

This behavioral ecology theory contributes to a better understanding of digital trust by raising awareness of the following details:

Pay attention to the context, actual value, and transparency.

An individual tries to satisfy their individual, current needs. Whether an online user is willing to provide personal data depends heavily on the goal he or she seeks to achieve by using a service or making a transaction. In the digital work, we most certainly don’t directly face an option that puts survival in jeopardy. However, we face obesity problems that can reach significant individual weight. When faced with a threatening deadline, a service from an online productivity tool can add considerable value. Furthermore, a customer needs to understand how the value offered correlates with the risk invested (reciprocity).

Pay attention to subjective variability.

The amount or expected value may differ from individual to individual. A young digital native may have a different interpretation of an option’s expected value than a digital immigrant. Hence, younger users may act more risk-prone just because they attribute lower subjective variability to an option. They just don’t care whether a service provides value. It’s always worth a try.

Pay attention to information asymmetry.

Incomplete, false, or partial information is a key challenge in online transactions. A service provider usually has more or better information than a customer. This information asymmetry needs to be removed through active communication (signaling). In particular, a service provider can signal consistent service quality – and therefore low variability in value – by enabling customer ratings and comments. The more ratings customers provide, the lower the perceived variability in service quality.

References Chapter 2:

Acquisti, A., Brandimarte, L., & Loewenstein, G. (2015). Privacy and human behavior in the age of information. Science, 347(6221), 509-514. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aaa1465

Acquisti, A., Taylor, C., & Wagman, L. (2016). The economics of privacy. Journal of Economic Literature, 54(2), 442-492. https://doi.org/10.1257/jel.54.2.442

Armstrong, G., Adam, S., Denize, S., & Kotler, P. (2014). Principles of marketing (6th ed.). Pearson.

Belk, R. W. (2013). Extended self in a digital world. Journal of Consumer Research, 40(3), 477-500. https://doi.org/10.1086/671052

De Keyser, A., Lemon, K. N., Klaus, P., & Keiningham, T. L. (2015). A framework for understanding and managing the customer experience. Marketing Science Institute Working Paper Series, 15(121), 1-47.

Denegri-Knott, J., & Zwick, D. (2012). Tracking prosumption work on eBay: Reproduction of desire and the challenge of slow re-McDonaldization. American Behavioral Scientist, 56(4), 439-458. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002764211429360

Duhachek, A. (2005). Coping: A multidimensional, hierarchical framework of responses to stressful consumption episodes. Journal of Consumer Research, 32(1), 41-53. https://doi.org/10.1086/426612

Dunbar, R. I. M. (1992). Neocortex size as a constraint on group size in primates. Journal of Human Evolution, 22(6), 469–493. https://doi.org/10.1016/0047-2484(92)90081-J

Gielens, K., & Steenkamp, J. B. E. M. (2019). Branding in the era of digital (dis)intermediation. International Journal of Research in Marketing, 36(3), 367-384. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijresmar.2019.01.005

Haidt, J. (2006). The happiness hypothesis: Finding modern truth in ancient wisdom. Basic Books.

Hartzog, W., & Richards, N. (2019). Privacy’s constitutional moment. Boston College Law Review, 61(2), 419-482.

Helbing, D. (Ed.). (2015). Thinking ahead – Essays on big data, digital revolution, and participatory market society. Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-15078-9

Hennig-Thurau, T., Malthouse, E. C., Friege, C., Gensler, S., Lobschat, L., Rangaswamy, A., & Skiera, B. (2010). The impact of new media on customer relationships. Journal of Service Research, 13(3), 311-330. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094670510375460

Holbrook, M. B., & Hirschman, E. C. (1982). The experiential aspects of consumption: Consumer fantasies, feelings, and fun. Journal of Consumer Research, 9(2), 132-140. https://doi.org/10.1086/208906

Kahneman, D. (2011). Thinking, fast and slow. Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

Kahneman, D., & Tversky, A. (1979). Prospect theory: An analysis of decision under risk. Econometrica, 47(2), 263–291. https://doi.org/10.2307/1914185

Kaptein, M., Parvinen, P., & Pöyry, E. (2015). The danger of engagement: Behavioral observations of online community activity and service spending in the online gaming context. International Journal of Electronic Commerce, 20(1), 50-75.

Kozinets, R. V. (2019). Consuming technocultures: An extended JCR curation. Journal of Consumer Research, 46(3), 620-627. https://doi.org/10.1093/jcr/ucz034

Kumar, V., & Pansari, A. (2016). Competitive advantage through engagement. Journal of Marketing Research, 53(4), 497-514. https://doi.org/10.1509/jmr.15.0044

Kumar, V., & Reinartz, W. (2016). Creating enduring customer value. Journal of Marketing, 80(6), 36-68. https://doi.org/10.1509/jm.15.0414

Kumar, V., & Shah, D. (2009). Expanding the role of marketing: From customer equity to market capitalization. Journal of Marketing, 73(6), 119-136. https://doi.org/10.1509/jmkg.73.6.119

Kumar, V., Jones, E., Venkatesan, R., & Leone, R. P. (2011). Is market orientation a source of sustainable competitive advantage or simply the cost of competing? Journal of Marketing, 75(1), 16-30. https://doi.org/10.1509/jm.75.1.16

Lamberton, C., & Stephen, A. T. (2016). A thematic exploration of digital, social media, and mobile marketing: Research evolution from 2000 to 2015 and an agenda for future inquiry. Journal of Marketing, 80(6), 146-172. https://doi.org/10.1509/jm.15.0415

Lawer, C., & Knox, S. (2006). Customer advocacy and brand development. Journal of Product & Brand Management, 15(2), 121-129.

Manoogian, A., & Benson, B. (2017, January, 8th). 4 conundrums of intelligence. Medium. https://medium.com/thinking-is-hard/4-conundrums-of-intelligence-2ab78d90740f

Martin, K. D., & Murphy, P. E. (2017). The role of data privacy in marketing. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 45(2), 135–155. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-016-0495-4

Martin, K. D., Borah, A., & Palmatier, R. W. (2017). Data privacy: Effects on customer and firm performance. Journal of Marketing, 81(1), 36-58. https://doi.org/10.1509/jm.15.0497

McKnight, D. H., Choudhury, V., & Kacmar, C. (2002). Developing and validating trust measures for e-commerce: An integrative typology. Information Systems Research, 13(3), 334–359. https://doi.org/10.1287/isre.13.3.334.81

Metcalfe, M., & Mischel, W. (1999). A hot/cool-system analysis of delay of gratification: Dynamics of willpower. Psychological Review, 106(1), 3–19. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.106.1.3

Mischel, W. (2014). The marshmallow test: Mastering self-control. Little, Brown and Company.

Morgan, R. M., & Hunt, S. D. (1994). The commitment-trust theory of relationship marketing. Journal of Marketing, 58(3), 20-38. https://doi.org/10.2307/1252308

Morris, J. W. (2015). Selling digital music, formatting culture. University of California Press.

Morris, J. W., & Powers, D. (2015). Control, curation and musical experience in streaming music services. Creative Industries Journal, 8(2), 106-122. https://doi.org/10.1080/17510694.2015.1090222

O’Doherty, J. P., Cockburn, J., & Pauli, W. M. (2013). Learning, reward, and decision making in the human brain. In P. W. Glimcher & E. Fehr (Eds.), Neuroeconomics: Decision making and the brain. 2nd ed., 419–436. Academic Press. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-416008-8.00022-3

Parasuraman, A., Zeithaml, V. A., & Malhotra, A. (2005). E-S-QUAL: A multiple-item scale for assessing electronic service quality. Journal of Service Research, 7(3), 213-233.

Parker, G. G., Van Alstyne, M. W., & Choudary, S. P. (2016). Platform revolution: How networked markets are transforming the economy and how to make them work for you. W. W. Norton & Company.

Payne, A., & Frow, P. (2005). A strategic framework for customer relationship management. Journal of Marketing, 69(4), 167-176. https://doi.org/10.1509/jmkg.2005.69.4.167

Payne, A., & Frow, P. (2017). Relationship marketing: Looking backwards towards the future. Journal of Services Marketing, 31(1), 11-15. https://doi.org/10.1108/JSM-11-2016-0380

Plassmann, H. (2017, October 10). The pain of paying. Conference presentation. Society for Neuroeconomics Annual Meeting, Toronto, Canada.

Plassmann, H., O’Doherty, J., Shiv, B., & Rangel, A. (2008). Marketing actions can modulate neural representations of experienced pleasantness. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 105(3), 1050–1054. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0706929105

Plassmann, H., Venkatraman, V., Huettel, S., & Yoon, C. (2015). Consumer neuroscience: Applications, challenges, and possible solutions. Journal of Marketing Research, 52(4), 427–435. https://doi.org/10.1509/jmr.14.0048

Richards, N. M., & Hartzog, W. (2019). Privacy’s trust gap. Yale Law Journal, 128(4), 1180–1247.

Richards, N. M., & Hartzog, W. (2020). The pathologies of digital consent. Washington University Law Review, 96(6), 1461-1503.

Riedl, R., & Javor, A. (2012). The biology of trust: Integrating evidence from genetics, endocrinology, and functional brain imaging. Journal of Neuroscience, Psychology, and Economics, 5(2), 63-91.

Rode, C., Cosmides, L., Hell, W., & Tooby, J. (1999). When and why do people avoid unknown probabilities in uncertain decisions? Testing some predictions from optimal foraging theory. Cognition, 72(3), 269–304. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0010-0277(99)00042-6

Rose, S., Clark, M., Samouel, P., & Hair, N. (2012). Online customer experience in e-retailing: An empirical model of antecedents and outcomes. Journal of Retailing, 88(2), 308-322. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretai.2012.03.001

Simon, H. A. (1982). Models of bounded rationality. MIT Press.

Simon, H. A. (1997). Models of bounded rationality: Empirically grounded economic reason (Vol. 3). MIT Press.

Stephens, D. W. (1981). The logic of risk-sensitive foraging preferences. Animal Behaviour, 29(2), 628–629. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0003-3472(81)80128-5

Szeliga, Michael (1996): Push und Pull in der Markenpolitik, Peter Lang Verlag, [online] https://www.peterlang.com/document/1068231.

Thaler, R. H. (2016). Misbehaving: The making of behavioral economics. W. W. Norton & Company.

Urban, G. L. (2004). The emerging era of customer advocacy. MIT Sloan Management Review, 45(2), 77-82.

Urban, G. L. (2005a). Don’t just relate – Advocate! Customer advocacy as a new paradigm for marketing. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Wharton School Publishing.

Urban, G. L. (2005b). Customer advocacy: A new era in marketing? Journal of Public Policy & Marketing, 24(1), 155-159.

Vargo, S. L., & Lusch, R. F. (2004). Evolving to a new dominant logic for marketing. Journal of Marketing, 68(1), 1-17. https://doi.org/10.1509/jmkg.68.1.1.24036

Verhoef, P. C., Broekhuizen, T., Bart, Y., Bhattacharya, A., Dong, J. Q., Fabian, N., & Haenlein, M. (2021). Digital transformation: A multidisciplinary reflection and research agenda. Journal of Business Research, 122, 889-901. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2019.09.022

Waldman, A. E. (2018). Privacy, notice, and design. Stanford Technology Law Review, 21(1), 74-127.

Wendel, S. (2020). Designing for behavior change: Applying psychology and behavioral economics. O’Reilly Media.

Wilson, H. J., & Daugherty, P. R. (2018). Collaborative intelligence: Humans and AI are joining forces. Harvard Business Review, 96(4), 114-123.

Wilson, H. J., Daugherty, P. R., & Morini-Bianzino, N. (2017). The jobs that artificial intelligence will create. MIT Sloan Management Review, 58(4), 14-16.

Zuboff, S. (2019). The age of surveillance capitalism: The fight for a human future at the new frontier of power. Public Affairs.