Chapter 1: Learn how pervasive consumer concerns about data privacy, unethical ad-driven business models, and the imbalance of power in digital interactions highlight the need for trust-building through transparency and regulation.

Chapter 8: Learn how AI’s rapid advancement and widespread adoption present both opportunities and challenges, requiring trust and ethical implementation for responsible deployment. Key concerns include privacy, accountability, transparency, bias, and regulatory adaptation, emphasizing the need for robust governance frameworks, explainable AI, and stakeholder trust to ensure AI’s positive societal impact.

Content in this chapter

- Defining Trust

- Introducing the Iceberg Trust Model

- 1. The Agency Layer: Trust Cues

- 2. The Engineering Layer: Social Adaptors and Social Protectors

- 3. The Governance Layer: Adaptive Trust Stewardship

- 4. The Institutional Layer: Trust Constructs

- The Trust Development Process: An Evolving Framework

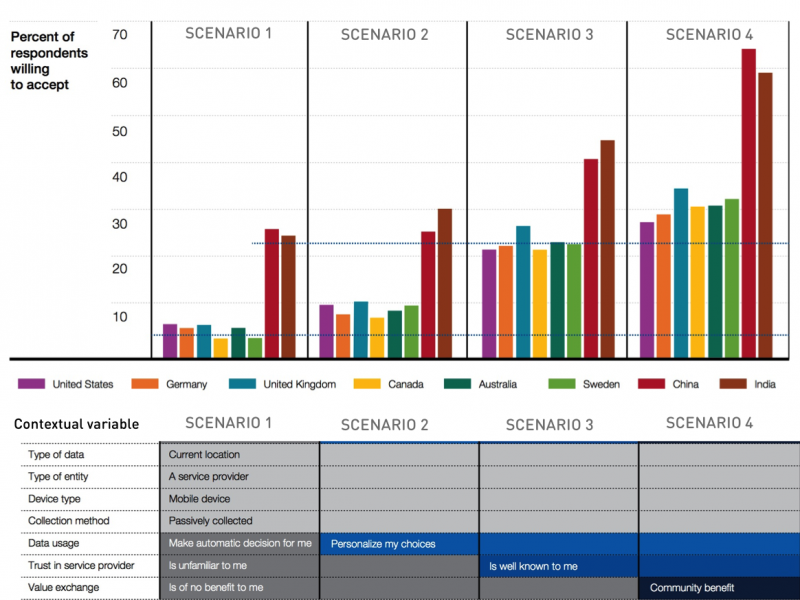

- Data Context

Today’s digital economy has an enormous potential to transform most of the aspects of our lives. The World Wide Web removes barriers to market entry, develops new, disruptive business models and eventually dissolves traditional values such as brick-and-mortar shops. Technology breaks the barriers between organizations, countries, and time zones. The way to modernity is characterized by a social change that “disembeds” individuals out of their traditional social relationships and localized interaction context (Giddens, 1995).

Every day, fresh start-up companies develop new perspectives on issues of our daily lives and propose often disrupting solutions. The consumer is faced with technologies and social concepts (such as the sharing economy) that are new and unknown. Digital trust disengages itself to an ever larger extent from the known concept of trust in persons and generalizes in institution-based trust (Luhmann, 1989). The iceberg approach to digital trust pays attention to different components of trust and provides a framework that allows marketing professionals to understand how trust is engendered.

Ever since the World Wider Web became a global phenomenon, scientists from a wide range of disciplines try to make the trust construct comprehensible. These studies all build on the broad scientific work from a more analogue world. Deutsch has developed one of the most fundamental definitions for trust (1962): He defines a framework in which an individual faces two aspects. First, the individual has a choice between multiple options that result in outcomes that it perceives as either positive or negative. Second, the individual acknowledges that the actual result depends on the behaviour of another person. Deutsch also mentions that the trusting individual perceives the effect of a bad result as stronger than the effect of a positive outcome. This corresponds to the findings of the prospect theory discussed in chapter 2.

Trust is the willingness of a party to be vulnerable to the actions of another party based on the expectation that the other will perform a particular action important to the trustor, irrespective of the ability to monitor or control that other party“.

(Mayer et al.)

Thus, trust is built if a person assumes the desired beneficial result is more likely to occur than a bad outcome. In this context, there is no possibility to influence the process. The following example illustrates this: a mother leaves her baby to a babysitter. She is aware that the consequences of her choice depend heavily on the behaviour of the babysitter. In addition, she knows that the damage from a bad outcome of this engagement carries more weight than the benefit of a good outcome. Important factors in the trust equation are missing control, vulnerability and the existence of risk (Petermann, 1985).

Multiple options and diverse scenarios lead to ambiguity and risk. According to Lumann, individuals must eventually reduce complexity to decide in such situations. Trust is a mechanism that reduces social complexity. This context is best captured in the definition of trust developed by Mayer, Davis and Schoorman (1995: 712).

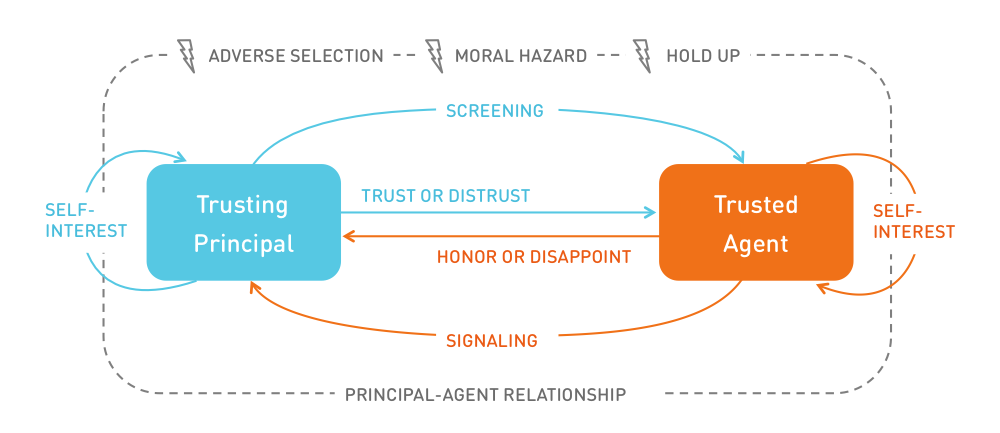

Trust can be an efficient help to overcome the agency dilemma. In economics, the principal-agent problem describes a situation where a person or entity (the agent) acts on behalf of another person (the principal). Due to information asymmetry, which is omnipresent in digital markets, the agent can either act in the interest of the principal or not by acting, for example, selfishly. Trust can solve such problems by absorbing behavioural risks (Ripperger, 1998). Screening and signalling activities are often inefficient in situations where information asymmetry exists due to high information costs. Trust can reduce such agency costs (including imminent utility losses). It can increase the agent’s intrinsic motivation to act in the principal’s interest.

You must trust and believe in people, or life becomes impossible.

(Anton Chekhov)

A trust relationship, as such, can be seen as a principal-agent relationship. The relationship between a trusting party and a trusted party is built on an implicit contract. Trust is provided as a down payment by the principal. The accepting agent can either honour this ex-ante payment or disappoint the principal.

According to the principle-agent theory a trusting party faces three risks:

Adverse Selection: When selecting an agent, the principal faces the risk of choosing an unwanted partner. Hidden characteristics of an agent or their service are not transparent to the principal before the contract is made. This leaves room for the agent to act opportunistically.

Moral Hazard: If information asymmetry occurs after the contract has been closed (ex post), the risk of moral hazard arises. The principal has insufficient information about the exertion level of the agent who fulfills the service. External effects, such as environmental conditions, can influence the agent’s actions.

Hold Up: This type of risk is particularly relevant for the discussion about the use of personal data. It describes the risk if the principal makes a specific investment, such as providing sensitive data. After closing the contract, the agent can abuse this one-sided investment to the detriment of the principal. The subjective insecurity about the agent’s integrity stems from potentially hidden intentions.

The described risks can be reduced through signalling and screening activities. Signalling is a strategy by which agents communicate their nature and authentic character. The provision of certification and quality seals is used to signal activities. On the other hand, a principal seeks to identify an agent’s true nature through screening activities. However, screening is only effective if signals are valid (the agent actually owns this characteristic) and if the absence of such a signal indicates the lack of this trait.

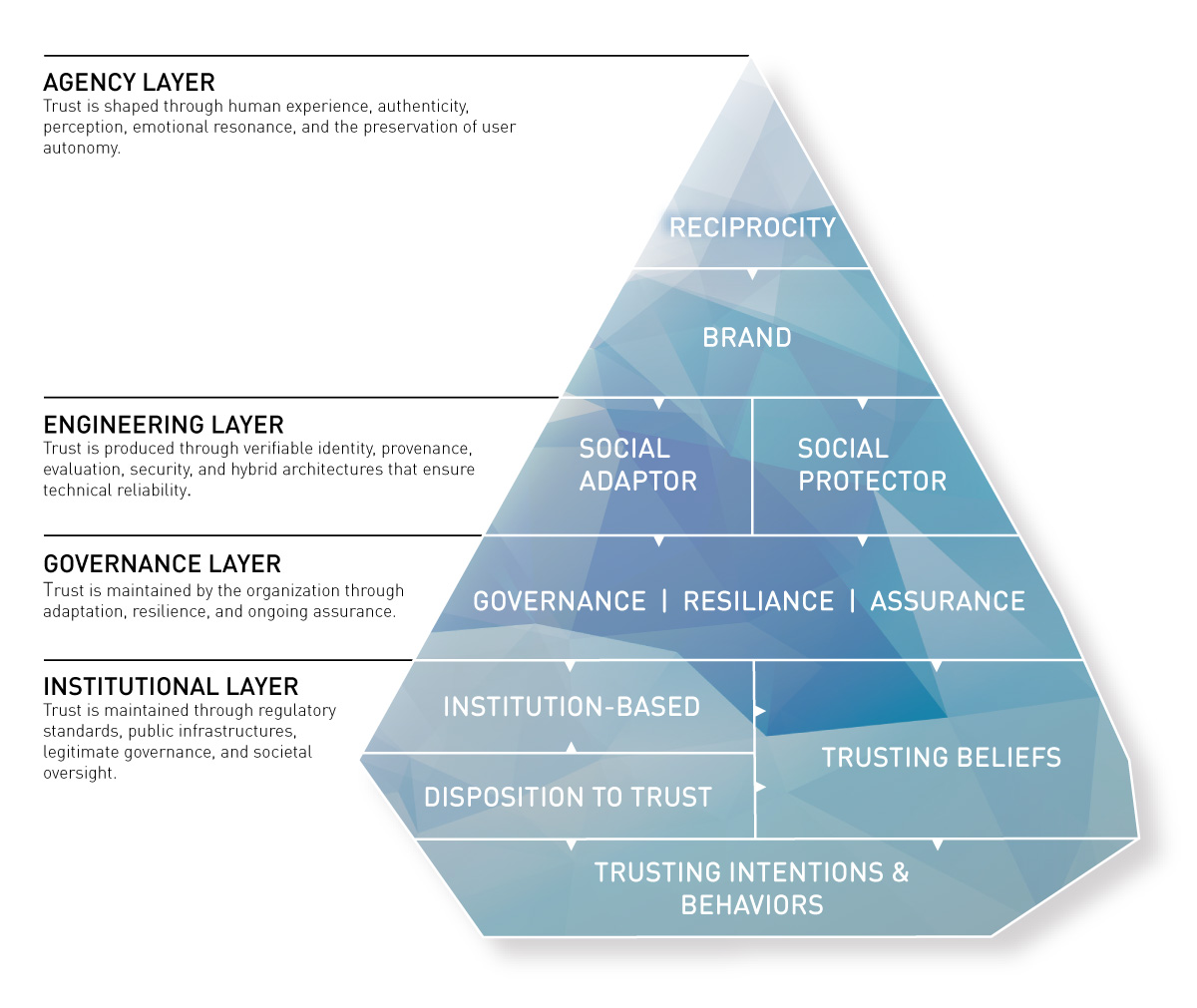

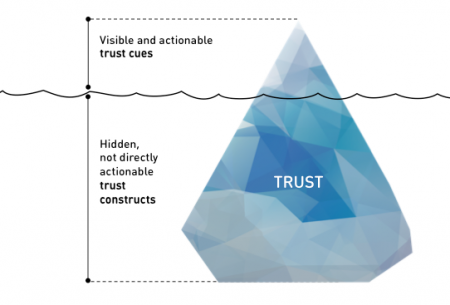

Our trust model resembles the shape of an iceberg. The iceberg metaphor works in many different ways:

First of all, trust must be seen as a precious good. It is hard to build, but it can be lost very quickly. This makes it both a key differentiator to win against the competition and a potential pitfall that can easily destroy organizations. The Volkswagen emissions scandal has demonstrated how quickly trust is lost. It showed that even strong brands from traditional brick-and-mortar businesses can become severely damaged. The Internet accelerates this process. Bad news or reviews are spread at light speed around the globe, and once negligible pieces of information can cause harmful shitstorms to spiral out of control. Like an iceberg in the open sea, trust issues must be recognized early, and marketers must sail elegantly around such perils. On the other hand, trust is vital. Ongoing melting of the polar ice caps will inevitably raise sea levels and put coastal areas at risk. Similarly, if the trust factor is neglected, organizations miss out on potential business opportunities and risk being sunk by the competition.

Second, the sheer size of an iceberg usually remains unknown to the observer. This is due to ice’s lower density than that of liquid water. Hence, only one-tenth of the volume of an iceberg is typically above the water level. This reflects that most of the determinants of trust are less known, not understood, or simply invisible. Moreover, it is difficult to manipulate those constructs. Trust, therefore, is often built when no one is looking. For companies, this means there are limited but essential options to address information asymmetry in digital markets.

Just like freezing water and forming an iceberg takes time, building trust usually takes time. The primary way to gain trust is to earn it by developing and nurturing relationships with customers and future prospects. Companies can and must have control over the quality and intensity of the customer experience if they want to influence the customer’s level of trust. Opportunities to shape the experience exist at touchpoints in the customer decision lifecycle. This model, however, focuses on understanding and engendering initial trust.

Trust is not generated through a single mechanism; it arises from the interaction of human perception, technical architectures, organisational safeguards, and institutional infrastructures. To understand how AI systems can be designed and governed responsibly, trust must be conceptualized as a multi-level socio-technical construct that involves human agency, engineering robustness, governance assurance, and institutional legitimacy. Trust-centric design sits at the intersection of these layers, translating structural guarantees into meaningful user experiences.

Trust-centric design serves as a bridge between human psychology, engineering infrastructure, and institutional governance. It translates deep structural assurances (identity, provenance, oversight) into signals that users can understand intuitively, making trust both visible and tangible. Effective trust-centric design requires clarity about authorship, contextual transparency, and visible human oversight. It must ensure that users feel empowered and respected, even when interacting with advanced automated systems.

This integrative perspective highlights that trust cannot be achieved through interface design, infrastructure, or regulation alone. Trust emerges only when the agency, engineering, governance, and institutional layers reinforce one another. When design aligns with verifiable architectures and legitimate governance, digital systems gain both emotional credibility and structural reliability.

The combined framework demonstrates that trustworthy AI requires coordination across three interdependent layers.

Human trust is strengthened when emotional cues align with structural assurances. Engineering trustworthiness is meaningful only when users understand and experience it. Institutional legitimacy is anchored in both broader societal expectations and long-term governance.

The iceberg model suggests four clusters of trust cues that sit at the tip of the iceberg: Reciprocity, brand, social adaptor, and social protector. Each cluster holds a set of trust signals or trust design patterns that marketing professionals can consider to engender trust. Chapter Two and the discussion of the principal-agent problem highlight the importance of trust cues in online transactions. “Perceptions of a trust cue trigger preestablished cognitive and affective associations in the user’s mind, which allows for speedy information processing” (Hoffmann et al., 2015, 142).

The iceberg framework identifies for each trust construct a set of 18 trust cues. The list was developed by first reviewing existing frameworks from the research literature and then integrating contemporary digital trust considerations. We applied the MECE principle to group cues into four distinct constructs, ensuring that each cue is uniquely placed while collectively covering the major aspects of digital trust. This method combines established ideas (such as transparency, warranties, and community moderation) with newer considerations (such as AI disclosures and quantum-safe encryption).

However, the list has limitations. It represents a snapshot in time and may not capture every emerging cue as digital trust evolves. Additionally, while the MECE framework helps clarify categories, some cues (e.g., 3rd party data sharing or sustainability commitments) can naturally span multiple constructs depending on context, and decisions on allocation involve some subjective judgment. This means the list should be seen as a flexible starting point for discussion rather than an exhaustive, immutable taxonomy.

Reciprocity:

Reciprocity is a social construct that describes the act of rewarding kind actions by responding to a positive action with another positive action. The benefits to be gained from transactions in the digital space originate in the willingness of individuals to take risks by placing trust in others who are regarded to act competently, benevolently and morally. A fair degree of reciprocity in the exchange of data, money, products and services reduces user’s concerns and eventually induces trust (Sheehan/Hoy, 2000). A user that provides personal data to an online service – actively or passively –perceives this as an exchange input. They expect an outcome of adequate value. A fair level of reciprocity is reached through the transparent exchange of information for appropriate compensation. The table below shows the most relevant signals or strategic elements that establish positive reciprocity.

Value & Fair Pricing

A business needs to offer fair reciprocal benefits directly relevant to the data it collects and stores. If the business uses information not necessary to the service being provided, additional compensation must be considered. Because of their bounded rationality, consumers are often likely to trade off long-term privacy for short-term benefits.

Eventually, trust is about encapsulated interest, a closed loop of each party’s self-interest.

Ensuring users/customers receive clear, tangible benefits (value) at a reasonable or transparent cost.

Engender: Users feel respected when transparent pricing aligns with the value delivered.

Erode: Hidden fees, overpriced tiers, or unclear costs can drive user frustration and distrust.

Transparency & Explainability

Fair and open information practices are essential enablers of reciprocity. Users must be able to quickly find all relevant information. This leads to a reduction in actual or perceived information asymmetry. Customer data advocacy can require altruistic information practices.

Disclosing policies, processes, and decision‐making (e.g., algorithms) clearly so users understand how outcomes or recommendations are reached. This includes fairness and transparency regarding 3rd-party data sharing.

Engender: Users appreciate open communication, which reduces suspicion.

Erode: Opaque “black box” operations lead people to suspect manipulation or unfair treatment.

Accountability & Liability

Users expect that access to their data will be used responsibly and in their best interests. If a company cannot meet these expectations or if an unfavourable incident occurs, businesses must demonstrate accountability. This requires processes and organizational precautions that enable quick, responsible responses.

Compliance is either a state of being in accordance with established guidelines or specifications, or the process of becoming so. The definition of compliance can also encompass efforts to ensure that organizations abide by industry regulations and government legislation.

In an age when platforms offer branded services without owning physical assets or employing the providers (e.g., Uber doesn’t own cars and doesn’t employ drivers), issues of accountability are increasingly complex. Transparency and commitment to accountability are increasingly strong indicators of trust.

. Being upfront about who is responsible when things go wrong and having mechanisms in place to take corrective action.

Engender: Owning mistakes and compensating users when appropriate builds trust.

Erode: Shifting blame or hiding mishaps erodes confidence and loyalty.

Terms & Conditions (Legal Clarity)

Standard legal information, such as Terms and Conditions and security and privacy policies, must be made proactively accessible. Users need to be informed about the information collected and used. The consistency of this content over time is an important signal that helps build trust.

Clearly stated user agreements, disclaimers, and legal obligations define the formal relationship between the company and the user.

Engender: Straightforward T&Cs (short, plain language) help users feel informed.

Erode: Long, incomprehensible, or deceptive “fine print” fosters suspicion.

Warranties & Guarantees

Warranties and guarantees support the perception of fair reciprocity and, therefore, signal trustworthiness. Opportunistic behaviour will entail expenses for the agent.

Commitments ensuring quality or functionality of products/services, often with money‐back or replacement policies.

Engender: Demonstrates company confidence in their offering, signaling reliability.

Erode: Denying legitimate warranty claims or offering poor coverage breaks trust.

Customer Service & Support

Pre- and after-sales service, as well as any other touch point that allows a user to contact an agent, is a terrific opportunity to shape the customer experience. Failures in this strategic element are penalized with distrust and unfavourable feedback.

Reliability is relatively easy to demonstrate online. It is critical to respond quickly to customer requests.

Responsive, empathetic help channels (phone, chat, email) that address user questions and problems effectively.

Engender: Timely, helpful support reassures users that the company cares about them.

Erode: Unresponsive or unhelpful support creates frustration and alienation.

Delivery & Fulfillment Excellence

Reliability, speed, and accuracy in delivering digital or physical products/services to end users.

Engender: Meeting (or exceeding) delivery promises confirms reliability.

Erode: Late or missing deliveries, or misleading timelines, undermine user confidence.

Refund, Return, or Cancellation Policies

Fair and user‐friendly processes for returns, refunds, or canceling subscriptions.

Engender: Demonstrates respect for user choice, reduces perceived risk.

Erode: Excessive hurdles, restocking fees, or strict no‐refund policies create mistrust.

This trust cue refers to the concept of social capital. This kind of capital refers to connections among individuals – social networks and the norms of reciprocity and trustworthiness that arise from them. The cue is similar to social translucence (please refer to the category “social protector”). However, it highlights instead the importance of the collective value rather than the social impact of certain behaviours.

- Algorithmic Fairness & Non‐Discrimination

- Proactive Issue Resolution Informed Defaults

- Recognition & Rewards (Loyalty Programs)

- Error & Breach Handling

- Dispute Resolution & Mediation

- User Education & Guidance

- Acknowledgment of Contributions

- Freemium & Subscription Transparency

- Micropayments & In‐App Purchases

- Fair refund or return policies

- Proactive communication on changes or updates

- User-friendly cancellation processes

- Clear explanations of how shared data is used to benefit the user

- Ethical handling of errors or breaches (e.g., transparent apologies and resolutions)

- Personalized user experiences based on shared data

- Consistent follow-through on promises

- Openness to user feedback and its implementation

- Efforts to educate users on data use and benefits

- Access to customer-friendly dispute resolution processes

- Transparency in pricing with no hidden fees

- Demonstrated commitment to sustainability or social good

- Frequent updates on the progress of services or orders

- Respect for user time with quick, accurate responses

- Accessible, clear opt-out options for data sharing

Brand

A second powerful signal promoting trusting beliefs is an entity’s brand. A company makes a specific commitment when investing in its brand, reputation, and awareness. Since brand building is a costly endeavour, consumers perceive this signal as very trustworthy. Capital invested in a brand can be considered a stake at risk with every customer interaction and transaction. Whether an investment pays off or is lost depends heavily on a company’s true competency. Strategic elements such as brand recognition, image, and website design should trigger associations in the user’s cognitive system that prompt a feeling of familiarity.

“Brands arose to compensate for the dehumanizing effects of the Industrial Age” (Rushkoff, 2017). They are essentially symbols of origin and authenticity.

Brand Image & Reputation

The identity of a company triggers associations that together constitute the brand image. It is the impression in the consumers’ minds of a brand’s total personality. Brand image is developed over time through advertising campaigns with a consistent theme and is authenticated through the consumers’ direct experience.

In the digital age, brands must focus on delivering authentic experiences and get comfortable with transparency.

Overall public perception of the brand’s character, reliability, and standing in the market.

Engender: Consistent positive image fosters user loyalty and pride in association.

Erode: Negative PR or repeated controversies undermine confidence.

Recognition & Market Reach

Brand recognition is the extent to which a consumer or the general public can identify a brand by its attributes, such as its logo, tagline, packaging, or advertising campaign. Frequent exposure has been shown to elicit positive feelings towards the brand stimulus.

Consumers are more willing to rely on large and well-established providers. Digital consumers prefer brands with a broad reach. Search engine marketing is a relevant element that influences a brand’s relevance and reach. Many new business models rely on a competitive advantage in the ability to generate leads through search engine optimization (SEO) and search engine advertising (SEA).

The degree to which the brand is widely known and recognized across regions and demographics.

Engender: Familiarity can reduce perceived risk and enhance trust.

Erode: If scandals or controversies accompany a wide reach, broad exposure amplifies distrust.

Familiarity & Cultural Relevance

Design Patterns & Skeuomorphism: Skeuomorphism makes interface objects familiar to users by using concepts they recognize. Use of objects that mimic their real-world counterparts in how they appear and/or how the user can interact with them. A well-known example is the recycle bin icon used for discarding files.

California Roll principle: The California Roll is a type of sushi developed to familiarize Americans with unfamiliar food. People don’t want something truly new; they want the familiar done differently.

Privacy by Design advances the view that the future of privacy cannot be assured solely by compliance with legislation and regulatory frameworks; rather, privacy assurance must become an organization’s default mode of operation. It is an approach to systems engineering that takes privacy into account throughout the whole engineering process. Privacy needs to be embedded by default throughout the architecture, design, and construction of the processes.

Design Thinking describes a paradigm – not a method – for innovation. It integrates human, business, and technical factors into problem formulation, problem solving, and design. The user (human) centred approach to design has been extended beyond user needs and product specification to include the „human-machine-experience“.

How naturally the brand’s products/services fit into local customs, language, and user contexts.

Engender: Users resonate with solutions tailored to their cultural norms.

Erode: Ignoring cultural nuances can lead to alienation or offense.

Personalized Brand Experience

Digital customers are very demanding about the relevance of a product, service, or piece of information. Mass customization and personalization foster a good customer experience. The ability to process large amounts of data enables individualized transactions and aligns production with pseudo-individual customer requirements.

Through personalization, a customer feels like they are being treated as a segment of one. Service providers can offer individual solutions and thereby increase perceived competency by providing better, faster access to relevant information. Personalization works best in markets with fragmented customer needs.

Tailoring brand touchpoints (marketing, app interactions) so users feel recognized as individuals.

Engender: Users appreciate relevant, personal engagement.

Erode: Over‐personalization or privacy intrusions can feel creepy or manipulative.

Brand Story & Narrative

Ever since the days of bonfires and cave paintings, humans have used storytelling to foster social bonding. Content marketing and storytelling done right are elemental means to engender trust. Well-constructed narratives attract attention and build an emotional connection. As trust in media, organizations, and institutions diminishes, stories offer an underappreciated vehicle for fostering these connections and, eventually, establishing credibility. Attributes of stories that build trust are genuine, authentic, transparent, meaningfu,l and familiar.

The brand’s history, origins, and overarching story that communicates purpose and authenticity.

Engender: A compelling, consistent narrative humanizes the brand and builds empathy.

Erode: Contradictions between stated story and actual practice (greenwashing, etc.) damage credibility.

Design Quality & Aesthetics

The quality of a brand’s digital presence (web, mobile, etc.) can foster brand reputation and enhance brand recognition. High site quality signals that the company has the required level of competence.

Important design qualities include usability, accessibility, and the resulting user experience.

A fundamental paradigm leading the design process is the process of “Privacy by Design”:

Privacy by Design advances the view that the future of privacy cannot be assured solely through compliance with legislation and regulatory frameworks; rather, privacy assurance must become an organization’s default mode of operation (privacy by default). It is an approach to systems engineering that takes privacy into account throughout the whole engineering process.

Privacy needs to be embedded by default throughout the architecture, design, and construction of the processes. The demonstrated ability to secure and protect digital data needs to be part of the brand identity.

Done right, this design principle increases the perception of security. This refers to the perception that networks, computers, programs, and, in particular, data are always protected from attack, damage, or unauthorized access.

The visual identity and user experience design that shape a recognizable “look and feel.”

Engender: High‐quality design suggests professionalism and attention to detail.

Erode: Shoddy, inconsistent, or dated design signals carelessness or lack of refinement.

Brand Consistency & Cohesion

Uniform messages, tone, and imagery across all channels (web, mobile, social media, physical stores).

Engender: Consistency implies reliability and coherence.

Erode: Inconsistent experiences (conflicting statements or design) can confuse and unsettle users.

Brand Ethics & Moral Values

The moral stance a brand publicly claims and consistently upholds (e.g., integrity, fairness, honesty).

Engender: Strong ethical standards reassure users of brand integrity.

Erode: Ethical lapses (cover‐ups, scandals) quickly destroy trust and cause reputational damage.

- Cultural or Societal Contributions

- Brand Purpose & Mission

- Awards and certifications related to brand excellence

- Heritage & Longevity

- Cultural or societal contributions tied to the brand (e.g., sustainability efforts)

- Brand heritage, Longevity or history of the brand in the market

- Localized content and design to resonate with diverse audiences

- Localized & Inclusive Expressions

- ESG & Sustainability Reporting

- Clear and compelling brand purpose or mission statement

- Branded or Immersive Experiences

- Consistent visual identity (color schemes, typography, etc.)

- Engaging and authentic social media presence

- DEI ( Diversity, Equity, Inclusion) & Accessibility Commitments

- Demonstrated innovation tied to the brand (e.g., patents or unique offerings)

- Ease of navigation and accessibility in digital touchpoints

- Commitment to inclusivity and diversity in branding

- Digital Experience Innovation

- Transparent leadership presence (e.g., active CEOs on social media)

- Political & Activist Stance

- Consistency in delivering on brand promises over time

- Exclusive branded experiences (e.g., events, limited editions)

- Social Impact “Score” or Recognition

- Iconic or easily recognizable brand symbols

Human perception alone cannot sustain digital trust without robust technical foundations. The engineering layer conceptualizes trust as a system property that must be measurable, auditable, and verifiable. Technical trust arises from mechanisms such as identity assurance, provenance tracking, cryptographic guarantees, adversarial evaluation, and resilient system architectures. These mechanisms act as social adaptors, reducing uncertainty, and as social protectors, preventing harm and misuse.

Modern AI systems introduce distinctive failure modes, including hallucinations, distributional drift, prompt injection, data leakage, and bias amplification, that require continuous evaluation throughout a system’s lifecycle (Antil, 2025; Amodei et al., 2016). Evidence-based controls such as anomaly detection, model monitoring pipelines, data provenance tracking, and bias audits convert trust from a narrative into a demonstrable system attribute.

Distributed digital ecosystems increasingly depend on decentralized trust infrastructures that provide cryptographically verifiable guarantees. Self-Sovereign Identity (SSI), verifiable credentials, and the Trust over IP (ToIP) stack enable privacy-preserving identity exchange and selective disclosure (W3C, 2021; ToIP, 2022). Standards such as C2PA, which enable content to be cryptographically signed at creation, establish provenance, mitigate deepfake-driven misinformation, and preserve epistemic trust online (C2PA, 2022).

Despite the flexibility of large neural models, many trust requirements, including rule consistency, auditability, and transparent reasoning, cannot be ensured by probabilistic systems alone. This limitation has accelerated the adoption of hybrid AI architectures that combine symbolic reasoning, deterministic rule engines, verifiable credential flows, and knowledge graphs with generative models (Marcus, 2020). Such hybrid approaches combine adaptability with predictability, thereby providing the technical reliability demanded in high-stakes or regulated domains.

Social adaptor

The social adaptor is a strategic element that connects the cues processed by the cognitive system with the base of the iceberg. It is an interface to the construct of institution-based trust. The social adaptor holds innovative strategic elements in the technological space that influence how consumers perceive structural assurance and situation normality. As outlined in Chapter 1, system complexity in a modern digital world increases on a factorial scale. Increasing system complexity, in turn, requires more decentralized control mechanisms (Helbing, 2015). This is why digital consumers must be given more control over their data. It is a matter of time before decentralized user control becomes a legal requirement.

By reinforcing structural assurance and situational normality, the Social Adapter connects to the institution-based trust at the base of the iceberg. Institution-based trust means the user trusts the institution or system because of its supportive structures and the broader context, even if they have no prior personal interaction with it. For instance, a new user on a platform might not yet trust the individual seller (no prior relationship), but if the platform offers strong structural assurances (e.g., escrowed payments, a money-back guarantee) and everything about the site feels “legit” and normal, the user’s institution-based trust is high. The Social Adapter encompasses “technological framework” elements that create this effect. We can think of it as trust by design: it’s about building the trust layer into the digital environment itself.

It’s important to note how the Social Adapter concept reflects a shift toward designing for trust in modern digital strategy. Many companies now invest in features such as two-factor authentication, user control panels for privacy settings, transparent explanations of AI decisions, and consistent user interface guidelines – all of which can be seen as Social Adapter tools that increase users’ confidence in the system. In summary, the Social Adapter is about embedding trustworthiness into the system’s architecture and user experience, so that even unseen processes (such as security algorithms or data-handling practices) translate into a sense of trust for users. Organizations can foster trust by proactively adopting and implementing effective social adapter strategies early and with care.

Industry experts increasingly describe digital trust as having two dimensions: explicit and implicit trust (Tölke, 2024). One hypothesis posits that “digital trust = explicit trust × implicit trust”, suggesting that both factors are essential and mutually reinforcing in creating overall trust. While this equation is more conceptual than mathematical, it conveys the idea that if either explicit or implicit trust is zero, the result (digital trust) will be zero.

Digital Trust = Explicit Trust × Implicit Trust

Explicit trust refers to trust that is consciously and deliberately fostered or signaled. It includes any action or information deliberately provided to engender trust. For example, when a platform verifies users’ identities or when a user sees a verified badge or signed certificate, those are explicit trust signals. In access management terms, explicit trust might mean continuously verifying identity and credentials each time before granting access, essentially a “never trust, always verify” approach. An example of explicit trust in practice is a reputation system on a marketplace: a buyer trusts a seller because the seller has 5-star ratings and perhaps a “Verified Seller” badge. That trust is explicitly cultivated through visible data. Another example is an AI system that provides explanations or certifications; a user might trust a medical AI’s recommendation more if an explanation is provided and if the AI model is certified by a credible institution (explicit assurances of trustworthiness).

Implicit trust, on the other hand, refers to trust that is built indirectly or in the background, often without the user’s conscious effort. It stems from the environment and behavior rather than overt signals. Implicit trust typically includes the technical and structural reliability of systems. For instance, a user may not see the cybersecurity measures in place, but if the platform has never been breached and consistently behaves securely, the user develops an implicit trust in it. As one industry report noted, “Implicit trust includes cybersecurity measures to protect digital infrastructure and data from threats such as hacking, malware, phishing and theft” (Tölke, 2024). Users generally won’t actively think “I trust the encryption algorithm on this website,” but the very absence of security incidents and the seamless functioning of security protocols contribute to their trust implicitly. Likewise, consistent user experience and adherence to norms (which tie back to situational normality) build implicit trust. Users feel comfortable and at ease because nothing alarming has happened.

In the field of recommender systems, the distinction between explicit and implicit trust has been studied to improve recommendations (Demirci & Karagoz, 2022). Explicit trust can be something like a user explicitly marking another user as trustworthy (as was possible on platforms like Epinions, where you could maintain a Web-of-Trust of reviewers). Implicit trust can be inferred from behavior. If two users have very similar tastes in movies, the system might infer a level of trust or similarity between them, even if they never explicitly stated it. Demirci & Karagoz have found that these two forms of trust information have “different natures, and are to be used in a complementary way” to improve outcomes (2022, 444). In other words, explicit trust data is often sparse but highly accurate when available (e.g., an explicit positive rating means strong declared trust). In contrast, implicit trust can fill in the gaps by analyzing behavior patterns.

Applying this back to digital trust broadly: Explicit trust × Implicit trust means that to achieve a high level of user trust, a digital system must provide tangible, visible assurances (explicit cues) and invisible, underlying reliability (implicit factors). If a system has only implicit trust (e.g., it’s very secure and well-engineered) but provides no explicit cues, users might not realize they should trust it. Users may feel uneasy simply because there are no familiar signals, even if it’s trustworthy under the hood. Conversely, if a system has many explicit trust signals but lacks actual implicit trustworthiness, users may be initially convinced, but that trust will erode quickly if something goes wrong. The combination is key: users need to see reasons to trust and also experience consistency and safety that justify that trust.

The Social Adapter component of the Iceberg Model, together with the Brand and Reciprocity cues, can be viewed as the embodiment of this dual approach. It provides the technological trust infrastructure (implicit) and often also interfaces with user-facing elements (explicit), such as interface cues or processes that make those assurances evident to the user. For instance, consider an online banking website. The Social Adapter elements would include back-end security systems, encryption, fraud detection (implicit trust builders), and front-end signals like displaying the padlock icon and “https” (encryption explicit cue), showing logos of trust (FDIC insured, etc.), or requiring the user’s OTP (one-time passcode) for login. When done right, the user both feels the site is safe (everything behaves normally and securely) and sees indications that it is trustworthy. In this way, the Social Adapter aligns with the idea that digital trust is the product of explicit and implicit trust factors working together.

It’s worth noting that in cybersecurity architecture, there has been a shift “from implicit trust to explicit trust” in recent years, epitomized by the Zero Trust security modelfedresources.com. Zero Trust means the system assumes no implicit trust, even for internal network actors – everything must be explicitly authenticated and verified. This approach was born of the realization that implicit trust (such as assuming anyone within a corporate network is trustworthy) can be exploited. While Zero Trust is about security design, its rise illustrates a broader trend: relying solely on implicit trust is no longer sufficient. Systems must continually earn trust through explicit verification. However, the end-user’s perspective still involves implicit trust; users don’t see all those checks happening, they simply notice that breaches are rare, which again builds their quiet, implicit confidence. Thus, even in a Zero Trust architecture, the outcome for a user is a combination of explicit interaction (e.g., frequent logins, multifactor auth prompts) and implicit trust (the assumption that the system is secure by default once those steps are done).

In summary, the hypothesis that digital trust equals explicit trust multiplied by implicit trust highlights a crucial principle: trust-by-design must operate on both the visible and the invisible planes. It’s not a literal equation for computing trust, but a reminder that product designers, security engineers, and digital strategists need to address human trust at both levels: by providing transparent, deliberate trust signals and by ensuring robust, dependable system behavior.

As digital ecosystems evolve, a growing chorus of experts argues that true digital trust will increasingly hinge on decentralized user control. In traditional, centralized models, users had to place significant trust in large institutions or platforms to serve as custodians of data, identity, and security. This aligns with what we discussed as institution-based trust (trusting the platform’s structures). However, recurring scandals have eroded confidence and exposed a key limitation: when a single entity holds all the keys (to identity, data, etc.), a failure or abuse by that entity can shatter user trust across the board. Empowering users with more direct control is emerging as a way to mitigate this risk and distribute trust.

One area where this philosophy is taking shape is digital identity management. The conventional approach to digital identity (think of how Facebook or Google act as identity providers, or how your data is stored in countless company databases) is highly centralized. Now, new approaches such as decentralized and self-sovereign identity (SSI) are shifting that paradigm.

In an SSI system, you might have a digital identity wallet that stores credentials issued to you (e.g., a digital driver’s license or a verified diploma). These credentials are cryptographically signed by issuers but are ultimately controlled by the user. By removing centralized intermediaries, users no longer need to implicitly trust a single middleman for all identity assertions; trust is instead placed in open protocols and cryptographic mathematics.

From a user’s perspective, decentralized identity and similar approaches can significantly enhance trust. First, privacy is improved because the user can disclose only the necessary information, or none at all (using techniques like selective disclosure or zero-knowledge proofs), rather than handing over full profiles to every service. Second, there’s a sense of empowerment: the user owns their data and keys. This aligns with rising consumer expectations and data protection regulations (such as GDPR) that promote greater user agency.

A Social Adapter in the modern sense might be a platform’s integration with decentralized identity standards. By doing so, the platform signals structural assurance in a new form: no single party (including the platform itself) can unilaterally compromise user identity, because identity is decentralized. It also contributes to situational normality over time, as these practices become standard and users become familiar with controlling their data.

Beyond identity, the theme of decentralization appears in discussions of trustworthy AI and data governance. For example, using decentralized architectures or federated learning can assure users that their data isn’t pooled on a central server for AI training, but rather stays on their device (enhancing implicit trust in how the AI operates). Similarly, blockchain technology is often touted as a “trustless” system. It aims to eliminate the need for blindly trusting a central intermediary. Trust is instead placed in a distributed network with transparent rules (the protocol code) and consensus mechanisms. When we say “trustless” in this context, it means the Social Adapter is the network and code itself. If well-designed, users implicitly trust the blockchain system due to its transparency and immutability, and explicit trust is further enhanced by the ability to verify transactions publicly.

It should be noted that decentralized approaches introduce their own complexities. Not every user wants, or is able, to manage private keys securely; for example, doing so introduces a new level of personal responsibility. A balance is needed: usability (which contributes to situational normality) must be designed hand in hand with decentralization. This is again where the Social Adapter plays a role: innovative solutions like social key recovery (where a user’s friends can help restore access to a wallet) or hardware secure modules in phones (to safely store keys) are being developed to make decentralized control viable and friendly. These are technological adaptations to social needs, encapsulated well by the Social Adapter idea.

In summary, the push for decentralized user control is a response to the erosion of trust in heavily centralized systems. By distributing trust and giving individuals more control over their identity and data, the structural assurance of digital services can increase, paradoxically by removing reliance on any single structure and instead trusting open, transparent frameworks. The implication for digital trust is profound: future trust signals might be less about “trust our company” and more about “trust this open protocol we’ve adopted” and “you are in charge of your information.”

If the last decade was about platforms asking users to trust them (often implicitly), the coming years may be about platforms empowering users so that less blind trust is needed. This evolution supports a more sustainable, user-centric approach to digital trust, where control and confidence grow together.

User Control & Agency

Companies can signal a willingness to empower users by providing measures of user control. Such measures can create the impression that an individual can actively reduce the risk of data abuse. Hence, a consumer perceives a lower transaction cost. This makes the transaction more attractive and, therefore, engenders trust.

An essential element of user control is the application of permission-based systems. Permissions must be based on the user’s dynamic consent. This consent involves a continuing obligation to comply with the user’s choice.

Allowing users meaningful control over their data, settings, and decisions (e.g., toggling features on/off).

Engender: Users feel respected and in command of their experience.

Erode: Overly restrictive or hidden controls make users feel exploited.

Identity & Access Management

Identity and Access Management (IAM) is a foundational element of digital security, enabling organizations and users to ensure that the right individuals access the right resources at the right times. As digital ecosystems grow increasingly complex, IAM has evolved beyond traditional username-password authentication to encompass a range of modern, trust-based solutions. “Digital identities are the backbone of a healthy digital society and are central to the future” (Tölke, 2024).

One emerging concept is Self-Sovereign Identity (SSI), which allows individuals to own and control their digital identities without depending on a central authority. SSI leverages cryptographic credentials stored in personal digital wallets, enabling users to selectively disclose information (e.g., proving age without sharing a birthdate). This model promotes privacy, portability, and user empowerment.

Meanwhile, e-ID systems are gaining traction globally. e-IDs are government-issued digital identities. Countries like Estonia and Switzerland (pending democratic approval) provide citizens with secure digital credentials that enable access to public and private services. These systems are often built on strong regulatory frameworks and enhance cross-border interoperability in digital interactions.

Another key trend is the rise of trust networks. These are ecosystems where multiple identity providers and relying parties collaborate under shared governance frameworks. They are certification programs that enable a party that accepts a digital identity credential to trust the identity, security, and privacy policies of the party that issues the credential and vice versa. Trust frameworks such as eIDAS in the EU or OpenID Connect help standardize how digital identities are issued, verified, and trusted across services and jurisdictions.

These innovations reflect a broader shift from centralized identity control toward user-centric, decentralized trust architectures. As IAM systems evolve, they must balance security, usability, and privacy, ultimately enabling safer and more seamless digital experiences for all participants in the digital economy.

With that, IAM contribute significantly to the concept of “explicit trust”. Please refer to Chapter 4, Recapturing Personal Data and Identity, for more details on digital identity.

Systems handling digital identities, login methods (passwordless, biometric), and user role permissions.

Engender: Convenient yet robust access management simplifies user journeys.

Erode: Poorly managed authentication or frequent hacking attempts alarm users.

Privacy Management & Consent Mechanisms

Privacy-Enhancing Technologies (PETs) are tools and methodologies designed to protect personal data, ensure confidentiality, and minimize the risk of unauthorized access or misuse. Some of the most critical technologies in this category are listed below as individual social protectors.

One of PETs’ primary functions is data minimization and anonymization, which help reduce the risk of re-identification in datasets. Technologies such as data masking replace or obscure sensitive information while preserving data usability. Tokenization substitutes sensitive data with non-sensitive placeholders, ensuring that real information is never exposed. Differential privacy introduces statistical noise into datasets to prevent the identification of individuals while still allowing functional analysis. Additionally, synthetic data generation produces artificial datasets that retain the statistical properties of real data while not revealing personal details.

Another critical area of PETs is secure data processing, which enables computations of sensitive data without exposure. Homomorphic encryption enables calculations to be performed directly on encrypted data, ensuring privacy throughout processing. Secure multi-party computation (SMPC) enables multiple parties to jointly compute a function without revealing their individual inputs. Trusted execution environments (TEEs) provide secure hardware-based enclaves where sensitive data can be processed without risk of exposure or tampering.

PETs also play a vital role in identity and access control, ensuring that personal data is protected during authentication and authorization processes. Zero-knowledge proofs (ZKPs) allow one party to prove knowledge of certain information without revealing the actual data. Self-sovereign identity (SSI) provides a decentralized model for digital identity, enabling individuals to control their personal information without relying on central authorities. Federated learning is another privacy-preserving technique that allows machine learning models to be trained across decentralized data sources without transferring raw data, thereby maintaining privacy while improving AI capabilities.

In the field of privacy-preserving data sharing, PETs facilitate secure collaboration without exposing raw data. Data clean rooms provide controlled environments where organizations can analyze shared datasets without revealing sensitive information. Private set intersection (PSI) enables two or more parties to compare their datasets and identify common elements without revealing the underlying data. These technologies are beneficial in sectors such as healthcare, financial services, and digital advertising, where data collaboration is essential but must be conducted in a privacy-compliant manner.

Clear, user‐friendly opt‐in/opt‐out choices regarding data sharing, advertising preferences, etc.

Engender: Transparent consent flows reassure users their info is handled ethically.

Erode: Hidden data collection or forced consent triggers privacy scandals.

Data Security & Secure Storage

Technical measures (encryption, secure servers) to protect user data from unauthorized access.

Engender: Strong security fosters a sense of safety and reliability.

Erode: Breaches or evidence of weak protection immediately compromise trust.

Trustless Systems & Smart Contracts

Trustless systems can replace the trust in an organization or the government with the cryptographic security of mathematics. Recent innovations in cryptocurrencies and the Blockchain protocol, in particular, enable avoiding the need for a trusted third party. Agency problems, such as moral hazard and hold-up, arise from imperfections in human nature. The cryptographic security of mathematics makes human interaction – the weakest link – obsolete.

The Blockchain protocol enables the trustless exchange of any digital asset, from domain name signatures, digital contracts, and digital titles to physical assets like cars and houses. Blockchain or decentralized approaches that reduce reliance on a single centralized authority.

Engender: Inherently transparent, tamper‐resistant processes can increase trust.

Erode: Over‐reliance on hype or confusing tech jargon can make adoption difficult.

Trust Influencers (Change Management)

Trust influencers are groups of people who can disproportionately influence a significant change in the way we evaluate situations, make decisions, and eventually act. They allow the masses (late adopters and laggards) to eventually make trust leaps by setting new social norms.

Although trust influencers show similarities to social media influencers, they draw on a different concept. Trust influencers can be compared to champions and agents defined by the Change Management Methodology.

Champions (or ambassadors) believe in and want the change and attempt to obtain commitment and resources, but may lack the sponsorship to drive it.

Agents implement change. Agents have implementation responsibility through planning and executing the implementation. At least part, if not all, of the change agent’s performance is evaluated and reinforced to support the success of this implementation.

Influencers gain their power from the theory of “social proof”. People tend to be willing to place enormous trust in the collective knowledge (wisdom) of the crowd.

Internal or external change agents who guide users to adopt new trust‐enabling tools or features.

Engender: Skilled communications and training build user confidence in novel systems.

Erode: Poor training or abrupt changes without explanation can spark backlash or confusion.

Compliance & Regulatory Features

Adhering to relevant standards (GDPR, HIPAA, PSD2, etc.) and providing user assurances about legal protections.

Engender: Legal compliance signals professionalism and readiness to protect user rights.

Erode: Noncompliance or constant regulatory fines erode trust in the brand’s reliability.

- Auditable Algorithms & Open‐Source Frameworks

- Zero‐Knowledge Proof & Privacy‐Enhancing Tech

- AI-powered personalized data control interfaces

- Adaptive Cybersecurity & Fraud Detection

- Trust Score Systems & Ratings

- Biometric authentication for enhanced security

- Regulatory compliance features integrated into platforms

- Privacy dashboards for user-friendly data control

- Adaptive cybersecurity systems to mitigate risks in real-time

- Auditable algorithms for ethical AI decision-making

- Open-source frameworks to promote transparency

- Integration of consent mechanisms into UX designs

- Federated learning models to secure data during machine learning

- User-centric trust score systems to indicate reliability

- Data portability tools for seamless transfers between services & Interoperability

- Customizable data-sharing preferences

- Multi-layered encryption for enhanced security

- Generative AI Disclosures

- Local‐First & Privacy‐Preserving Analytics

- Algorithmic Recourse & Appeal

- Quantum‐Safe or Advanced Encryption

- Data Minimization by Design

Social protector

The empowered customer has identified online review systems as a very intuitive, robust, and helpful source of information for decision-making. Uncountable amounts of ratings and reviews are posted every day. Given the enormous size of their communities, consumer websites that rely on reputation systems are among the most frequently visited pages on the World Wide Web. Cues within the cluster of social protectors can support users to avoid lossy interactions. They can help to overcome the ‘tragedies of the commons’ and create social benefits.

Affiliation & Sense of Belonging

In contrast to a lock-in strategy, companies can build customer loyalty by focusing on values customers can relate to. Whereas the element of personalization is highly effective from a signalling perspective, developing a feeling of affiliation and belonging can be successful from a screening perspective. “The feeling of belonging to a community, which deepens over time, leads to positive emotions and positive evaluation of the group members, generating a communal sense of trust (Einwiller et al. 2000: 2).

Fostering a community where users feel they share identity or values with peers or the brand.

Engender: Emotional bonds create loyal user bases willing to defend the brand.

Erode: If users feel excluded or unwelcome, they lose interest and trust.

Reputation Systems & 3rd‐Party Endorsements

Reputation can be considered a collective measure of trustworthiness – in the sense of reliability – based on the referrals or ratings from members of a community (Josang et al., 2007). Signals from reputation systems are among the most popular elements that web users screen. The growing familiarity of users with these mechanisms is both a benefit and a risk. Reputation systems are not immune to manipulation.

Valuable reputation information is embodied in a person’s social graph. The latter refers to the connections between an individual and the other people, places, and things it interacts with within an online social network. Keep in mind that trust usually lies within the group with the expertise rather than the group with a similar need.

Third-party endorsements are primarily independent statements by certification authorities or other experts attesting to honesty and trustworthiness. They usually facilitate the transfer of positive cognitive associations with the endorser to the endorsee. Signalling objective security measures through 3rd-party certificates or guarantees enhances a sense of security and builds trust.

Because of their high potential to increase communication persuasiveness, companies can also draw on heuristic cues as communicators (Eagly & Chaiken, 1993). These are cues that are based on experience or common sense. Their use is intended to save time and reduce the need for thinking. Examples are experts, attractive persons, or majorities.

Social media influencers are a new kind of endorsers. They indicate the increasing importance of collective experience (vs. personal experience) on trust. People tend to trust messages from people they know (e.g., friends and family). That’s why word-of-mouth marketing is a powerful means to engender trust (refer also to social adaptors, such as trust influencers).

Tools (e.g., star ratings) or external seals of approval (media, NGOs) that validate trustworthiness.

Engender: Peer and expert endorsements reduce uncertainty about the brand/product.

Erode: Fabricated or misleading endorsements can quickly backfire when exposed.

Brand Ambassadors & Influencer Partnerships

High‐profile figures who publicly support or advocate for the brand, shaping community perceptions.

Engender: Trusted advocates expand credibility and reach.

Erode: Misaligned influencers (e.g., involved in controversies) can tarnish the brand by association.

Customer Testimonials & User‐Generated Content

Real user reviews, stories, images, or videos that speak to product/service quality.

Engender: Authentic voices reassure others about genuine brand value.

Erode: Suspicion of fake or paid reviews undermines the community’s trust.

Community Moderation & Governance

Systems and guidelines that maintain respectful, constructive user interactions (e.g., content guidelines, warnings).

Engender: Well‐run moderation fosters a safe and positive community.

Erode: Inconsistent or heavy‐handed moderation alienates users, while no moderation leads to toxic environments.

Social Translucence & “Social Mirror”

In the digital space, we often lack the many social cues that tell us what’s happening. For example, if we return shoes bought in Zalando, we will take the parcel to the next post office. Upon scanning the package, we are handed a receipt. Such physical cues are typically missing in online transactions. Social translucence is an approach to designing systems that support social processes. Its goal is to increase transparency by making properties of the physical world that support graceful human-human communication visible in digital interactions (Erickson, T., Kellogg, W. A., 2000).

Translucence can be taken to the next level by confirming a person’s online identity by matching it to offline ID documents, such as a driver’s license or passport (e.g., Airbnb’s Verified ID).

Making community interactions visible enough that norms, accountability, and reputation form naturally, without exposing private data.

Engender: Users behave more civilly when feedback loops (likes, flags) are transparent.

Erode: Overly anonymous or opaque systems can foster trolls, abuse, or “bad actor” behavior.

- Events & Sponsorships

- Sentiment Analysis & Social Listening

- Media Coverage & Press Mentions

- Comparative Benchmarks & Reviews

- Trusted third-party verification seals (e.g., “Verified by…”)

- Positive media coverage or press mentions

- Customer testimonials highlighting brand reliability

- Fake‐Review Detection & Misinformation Safeguards

- Influencer partnerships aligned with the brand identity

- User-driven content showcasing brand loyalty (e.g., UGC campaigns)

- Strong presence in community events or sponsorships

- Prominent brand ambassadors or advocates

- Verified user badges to authenticate review contributors

- Flagging and reporting mechanisms for false or abusive reviews

- Real-time user feedback loops for emerging trends or issues

- Transparency on reviewer identity or experience level

- Historical performance ratings of products or services

- Review timestamps for relevance and recency

- Highlighting helpful or high-quality reviews through voting systems

- AI-driven fake review detection

- Highlighting community-driven best practices or guides

- Transparency of review guidelines or moderation rules

- Comparative benchmarks of performance within categories

- User reputation scores based on activity or expertise

- Automated/Crowdsourced Content Moderation

- Community Voting & Collective Decision‐Making

- Co‐creation & Community Engagement

- Incentives for honest and high-quality reviews (e.g., points or badges)

- Alerts for inconsistencies or anomalies in review patterns

- Publicly accessible community standards or charters

- Block/Ignore & Safe‐Space Features

- Public Interest & Crisis‐Response Alerts

- Cross-platform integration of reputation (e.g., LinkedIn or GitHub scores)

- Real‐Time Fact‐Checking & Community Alerts

T he governance layer forms the organizational backbone of digital trust. Governance determines whether systems are operated responsibly, monitored continuously, and adapted to evolving risks and societal expectations. Traditional governance, risk, and compliance (GRC) structures assume stable processes, linear causality, and periodic oversight. These assumptions break down in complex digital environments characterized by emergent behaviors, interconnected risks, and rapidly evolving AI systems (Snowden & Boone, 2007; Dekker, 2011).

Modern governance must therefore be adaptive rather than prescriptive. Research in complexity science, resilience engineering, and socio-technical systems demonstrates that trustworthy organizations continuously sense their environment, detect weak signals, coordinate across functional boundaries, and update governance controls dynamically (Hollnagel et al., 2006; Woods, 2015). This shift aligns with recent frameworks advocating Governance–Resilience–Assurance (GRA) rather than GRC as the appropriate structure for digital ecosystems (Bengio et al., 2025; Linkov & Kott, 2019).

Three governance capabilities are critical:

Adaptive Governance

Adaptive Governance ensures that policies, design requirements, and operational practices evolve in response to emerging risks, public expectations, and regulatory change. Studies in digital governance emphasize the need for continuous policy updating, participatory decision-making, and alignment with organizational values (Floridi & Cowls, 2019).

Organizational Resilience

Organizational Resilience enables systems and teams to absorb disruptions, recover quickly, and maintain dependable service. Evidence from resilience engineering and cybersecurity research shows that resilient organizations prevent minor incidents from escalating, learn from near misses, and maintain graceful extensibility under stress (Hollnagel, 2011).

Continuous Digital Assurance

Continuous Digital Assurance refers to the set of evidence-producing mechanisms that demonstrate an AI system is functioning safely, fairly, and as intended. Techniques such as runtime monitoring, drift detection, explainability analysis, and automated compliance checks transform assurance from a periodic activity into an ongoing governance function (NIST, 2023; Raji et al., 2020). In contemporary AI governance, assurance is no longer treated as a one-off validation step but as a continuous socio-technical process embedded throughout the AI lifecycle.

Institutional Legitimacy and Collective Governance

Trust also depends on how societies govern AI systems and the infrastructures underlying them. The institutional layer provides the macro-level safeguards (e.g., legal frameworks, regulatory regimes, standards bodies, certification mechanisms, and public infrastructures) that ensure trust does not rely solely on private organizations. Digital identity frameworks, safety regulations, and cross-border interoperability rules illustrate how institutions establish rights, obligations, and protections.

Recent regulatory developments, such as eIDAS 2.0, the EU AI Act, and Switzerland’s AI Action Plan, demonstrate that governments increasingly view digital trust as a public good that requires coordinated action (European Parliament & Council, 2024; Hyseni, 2023; FINMA, 2024). These institutional frameworks establish several structural requirements:

- They articulate clear governance obligations and accountability expectations for AI operators.

- They mandate transparency, safety, and risk-management practices enforceable by audits and penalties.

- They ensure interoperability and cross-border trust, enabling stable digital ecosystems.

- They protect societies against discrimination, surveillance, and misuse of personal data.

Institutional trust must also be future-safe. Public rejection of previous identity initiatives (such as Switzerland’s initial e-ID proposal) revealed that trust depends not only on present safeguards but on credible protection against future misuse. Research confirms that public trust in AI remains low, especially in advanced economies, and that citizens strongly support robust governance and regulatory oversight. Institutional legitimacy, therefore, requires safeguards that remain credible across political cycles and technological change. This call to action is supported by current research on public attitudes toward AI; Lockey and Gillespie find, in their large survey across 17 countries, low levels of public trust and acceptance of AI systems, particularly in advanced economies (2025). They find a “clear public mandate for robust governance and regulation of AI systems to mitigate risks and universal endorsement of the principles and practices of trustworthy AI across countries (Lockey & Gillespie, 2025, p.279).

The iceberg trust model differentiates between two major components that influence the formation of initial trust: trust constructs and cues/signals. Trust constructs refer to elements of the iceberg that are usually underwater. They represent the schemata that unconsciously steer our behavior. Constructs represent mechanisms driven by our hot system (see Chapter 2 for more insights into the mind of the digital consumer).

Cues or signals refer to strategic areas and design patterns companies apply to engender trust. They are above the surface and help reduce information asymmetry, as outlined in the discussion of the principal-agent theory.

The model described hereafter is primarily influenced by recent research from local institutions, such as the University of St. Gallen (Hoffman et al., 2015) and the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology in Zurich (Helbing, 2015). Furthermore, it is built on the foundation of social cognitive theory. As outlined in the last chapter, cognitive structures allow for orientation in complex decision-making situations. However, the resulting behaviours are not always rational because individuals are influenced by cognitive biases.

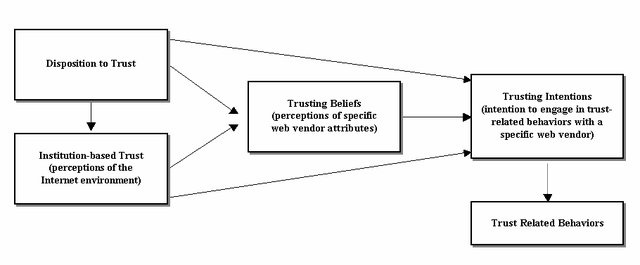

McKnight et al. (2002) provide a beneficial model for initial trust. Analyzing the broader literature on trust in the context of new communication technologies, they found that most established models share a combination of trusting dispositions, cognition, and willingness/intentions. Furthermore, they draw on the Theory of Reasoned Action to structure their argumentation. The theory shows that trust formation follows a catenation process. Beliefs lead to attitudes, which lead to behavioural intentions and behaviour itself.

The base of the iceberg comprises four primary constructs. Together, they describe the catenated process that forms trust and leads to trusting behaviours:

Institution-based trust:

“Institutional safeguards”

The first element that constitutes the underwater body of the iceberg is the belief that the necessary structural conditions for a positive outcome are present. This element includes requirements for a structure that makes an environment trustworthy. Such a structural element is legal protection. A decent legal framework that protects privacy supports the belief in a favourable system. McKnight compares this mechanism that can make the World Wide Web a more trusted environment with the effects of establishing justice and protection in the “wild, wild west” of the 19th century. This structural assurance makes users believe that structures are in place to promote success. A second dimension of institution-based trust is situation normality. Online users who perceive high situation normality would expect, in general, that vendors in the environment possess the required trust-building attitudes: competence, benevolence, and integrity.

Disposition to trust:

“Trust predisposition”

The individual disposition to trust describes the extent to which an individual is willing to depend on the actions of others. This propensity is inherent in any actor in a very individual way. “All trust begins and ends with the self […]” (Kahre/Rifkin, 1997: 81). Reception of stimuli and information is influenced by a person’s attitude. In addition, individual characteristics such as age, education, and income can affect the disposition to trust.

McKnight distinguishes two subconstructs of this disposition: Faith in humanity and a trusting stance. With high faith in humanity, a person assumes that others are usually upright, well-meaning, and dependable. A trusting stance means that an actor optimistically assumes a better outcome from an interaction than he would expect based on the characteristics of the agent. Principals may trust until they are proven wrong. Obviously, trust-building strategies may differ depending on the level of trust disposition. Some users are more suspicious than others. The level of disposition to trust influences institution-based trust.

Trusting beliefs:

“Trustworthiness perceptions”

These beliefs describe the actual perceptions of specific attributes of web vendors. According to the cognitive-based trust literature, trusting beliefs may form quickly. This process is heavily influenced by the individual disposition to trust as well as by the level of institution-based trust. A user believes that the trustee has attributes that benefit him. Obviously, many attributes can be considered beneficial. The most prominent ones are beliefs about competence, benevolence, and integrity. These are the main, specific attributes E-Commerce users tend to focus on to gauge vendors. Empirical data show that trusting beliefs demonstrate statistical separation. “[…] it is possible for a consumer to believe quickly that a Web-based vendor is honest and benevolent, but not competent enough to earn the consumer’s business or vice-versa (McKight, 2002, 352). The trusting beliefs differ over time. This gives room to shape customer experience as the relationship matures.

Trusting intentions and behaviours:

“Trust readiness”

Influenced by all three constructs mentioned above, a user may build an intention to engage in a trust-related behaviour and eventually act. This construct bridges the gap between cognitive assessments (trusting beliefs) and observable trust actions. Disclosing personal information to an online vendor constitutes a trust-related behaviour, as it demonstrates a willingness to be vulnerable to the vendor’s handling of sensitive data.

Relationships Between the Constructs

These four constructs relate to each other in important ways within McKnight’s framework:

-

- Institution-based trust and disposition to trust serve as antecedents that influence trusting beliefs, particularly in new relationships where specific information about the trustee is limited.

- Trusting beliefs (perceptions of trustworthiness) then lead to trusting intentions (willingness to be vulnerable), which in turn influence actual trusting behaviors.

The framework acknowledges that trusting intentions can form quickly, even in initial interactions, through cognitive processes such as categorization (stereotyping, reputation) and illusions of control, especially when supported by strong institutional safeguards. This detailed conceptualization helps explain how substantial levels of initial trust can exist without prior experience with a specific trustee, addressing a phenomenon that earlier trust models did not fully account for.

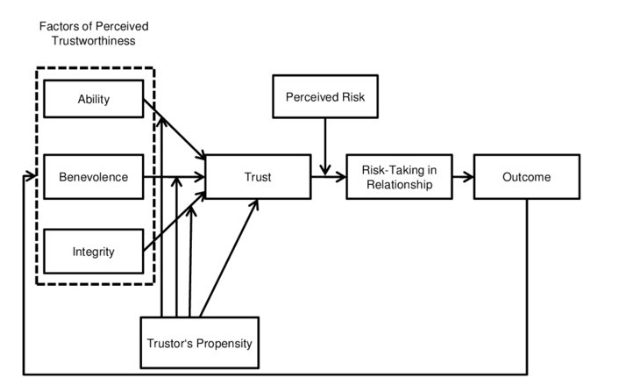

Trust is a fundamental element in human interactions, and it plays a crucial role in organisational behaviour, business relationships, and, more recently, human-technology interactions. Understanding how trust develops and evolves has been a significant focus of research across multiple disciplines. This section synthesises three significant theoretical contributions to trust development:

-

- Mayer, Davis, and Schoorman’s (1995) integrative model of organisational trust

- McKnight, Choudhury, and Kacmar’s work on initial trust formation (2002)

- Schlicker and colleagues’ recent Trustworthiness Assessment Model (2023, 2025)

Together, these frameworks provide a comprehensive understanding of the trust development process.

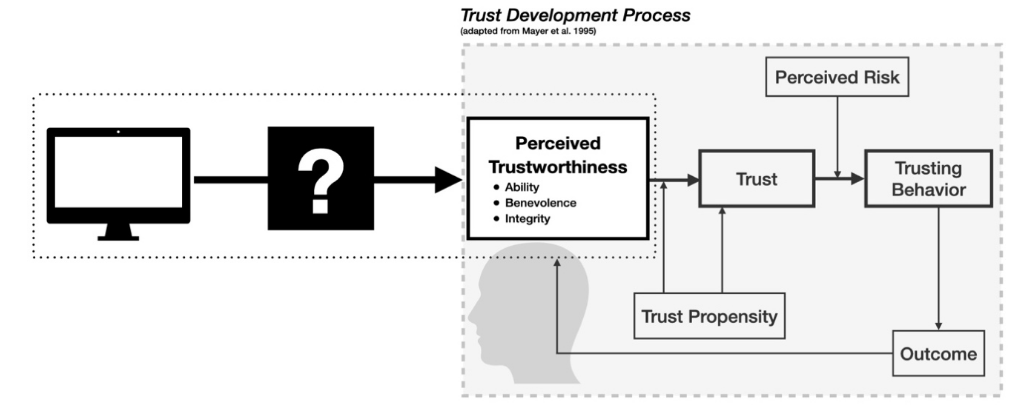

Mayer, Davis, and Schoorman’s Foundational Trust Model

In their seminal work, Mayer, Davis, and Schoorman (1995) proposed an integrative model of organisational trust that has become foundational in the field. They defined trust as “the willingness of a party to be vulnerable to the actions of another party based on the expectation that the other will perform a particular action important to the trustor, irrespective of the ability to monitor or control that other party” (p. 712). This definition explicitly highlights vulnerability as the critical element that distinguishes trust from related constructs such as cooperation or confidence.

The model identifies several key components in the trust development process:

First, it recognises the importance of the trustor’s propensity to trust. This propensity is a stable personality trait that represents a general willingness to trust others across situations. It influences how likely someone is to trust a trustee before receiving information about them.

Second, Mayer et al. identified three characteristics of trustees that determine their trustworthiness: ability (domain-specific skills and competencies), benevolence (the extent to which a trustee wants to do good for the trustor), and integrity (adherence to principles that the trustor finds acceptable). These three factors collectively account for a substantial portion of perceived trustworthiness.

Third, the model distinguishes between trust itself (the willingness to be vulnerable) and risk-taking in a relationship, which refers to the actual behaviours that make one vulnerable to another. A key insight is that trust leads to risk-taking behaviours only when trust exceeds the perceived risk threshold in a given situation.